SSD Overclocking – Not only possible, but doable at home!

In today’s article, we will do something unprecedented that I believe has not been done before. Many years ago, Intel had released an SSD capable of overclocking but only as a demonstration and today, we will use a 2.5″ SATA SSD that I acquired for this overclocking project. But before that, let’s take a look at the specifications of this SSD.

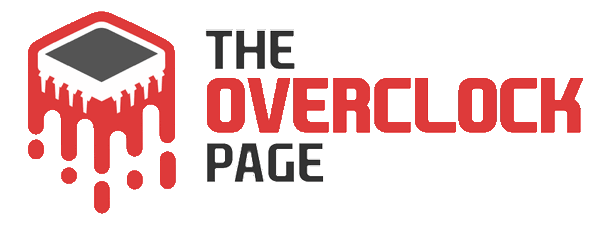

SPECIFICATIONS OF THE “GUINEA PIG” SSD

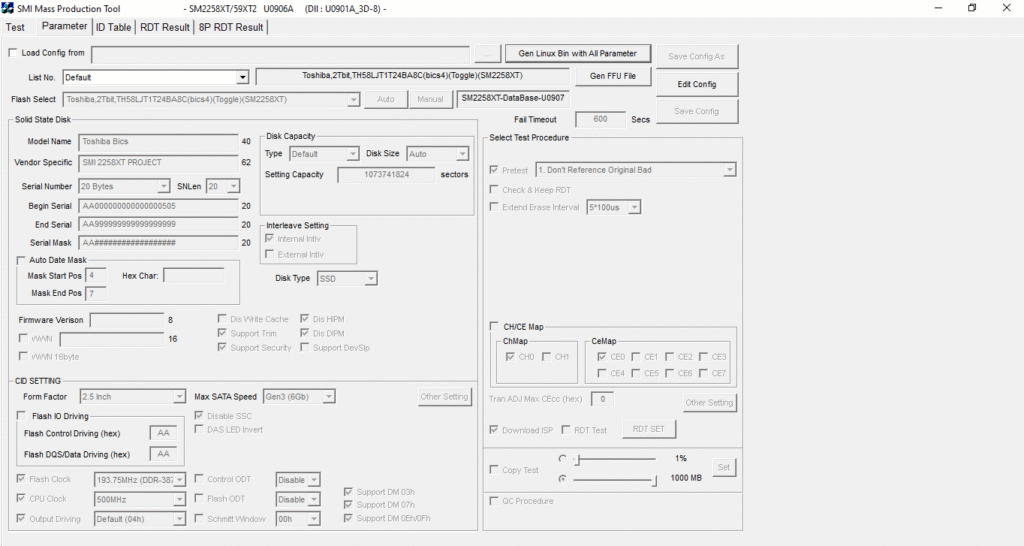

As we can see above, I choose an SSD based on a Silicon Motion controller as it makes this process much easier. It is possible to do with other controllers and NAND Flash, but some are much more complicated and require a lot more time and knowledge.

I DO NOT RECOMMEND THIS

What I am doing is purely for curiosity and serves to show that it is possible, but it is totally not recommended. Overclocking very sensitive components like NAND Flash can lead to serious problems, such as data corruption, due to the significant increase in read and write errors. It also increases thermal dissipation of energy in the form of heat and electrical consumption.

NECESSARY TOOLS

To perform this procedure, it was necessary to use an adapter that we have already seen on the website, which I bought on AliExpress. It is a SATA to USB 3.0 adapter with the Jmicron JMS578 bridge chip.

In addition to this clamp, as we can see, to short the terminals of the ROM/Safe Mode on the SSD PCB.

HOW THE OVERCLOCK WAS DONE

For security reasons, I cannot show the step-by-step process of how it’s done as users with less knowledge might try to replicate this and end up damaging the SSD, causing it to stop working and it also will void the manufacturer’s warranty as we are flashing a custom firmware onto the SSD, which the manufacturer does not allow.

But then you may ask me, Gabriel, why didn’t you choose an NVMe SSD? This happened because all the other NVMe SSDs I found already had their controller and NAND Flash set to the maximum frequency, which can still be increased, but the chance of success is much, much lower.

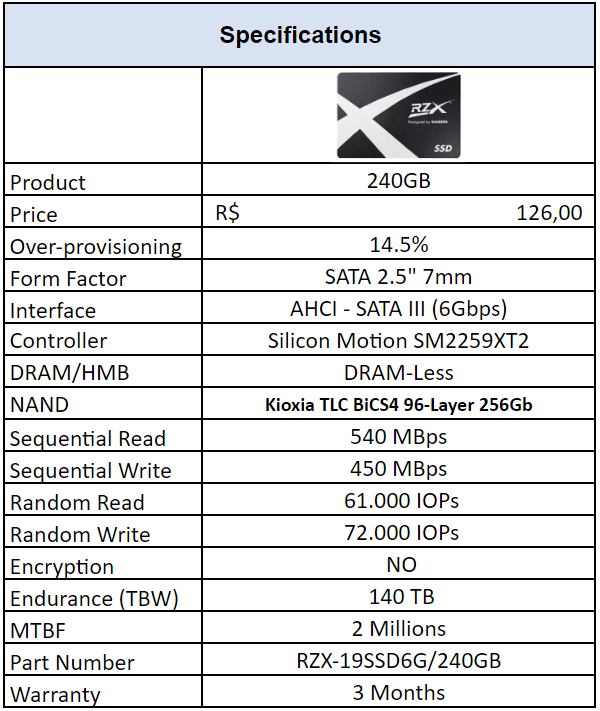

In this case, as we saw in the specifications tab, the SSD used has as its main controller the Silicon Motion SM2259XT2, which is a new variant of the SM2259XT.

CONTROLLER

The SSD controller is responsible for managing data, over-provisioning, garbage collection, among other background functions. And, of course, this ensures that the SSD performs well.

In this project, the SSD uses the Silicon Motion controller model SM2259XT2, which is a new variant of the SM2259XT.

In this case, it is a single-core controller, meaning it has only 1 main core responsible for managing the NANDs, with a 32-bit ARC architecture instead of the more common ARM architecture. This controller has an operating frequency that goes up to a maximum of 550 MHz, but as we will see in the following image, in this project, it was operating at 425 MHz.

This controller also supports up to 2 communication channels with a bus speed of up to 800 MT/s. Each of these channels supports up to 8 Chip Enable commands, allowing the controller to communicate with up to 16 Dies simultaneously using the Interleaving technique.

What was different from its predecessor, the SM2259XT, which had 4 channels and 4 C.E., supporting a maximum of 16 dies.

DRAM Cache or H.M.B.

Every top-of-the-line SSD that aims to deliver high and consistent performance requires a buffer to store its mapping tables (Flash Translation Layer or Look-up table). This allows the SSD to achieve better random performance and be more responsive.

Being a DRAM-Less SATA SSD, it does not support HMB (Host Memory Buffer) technology.

NAND Flash

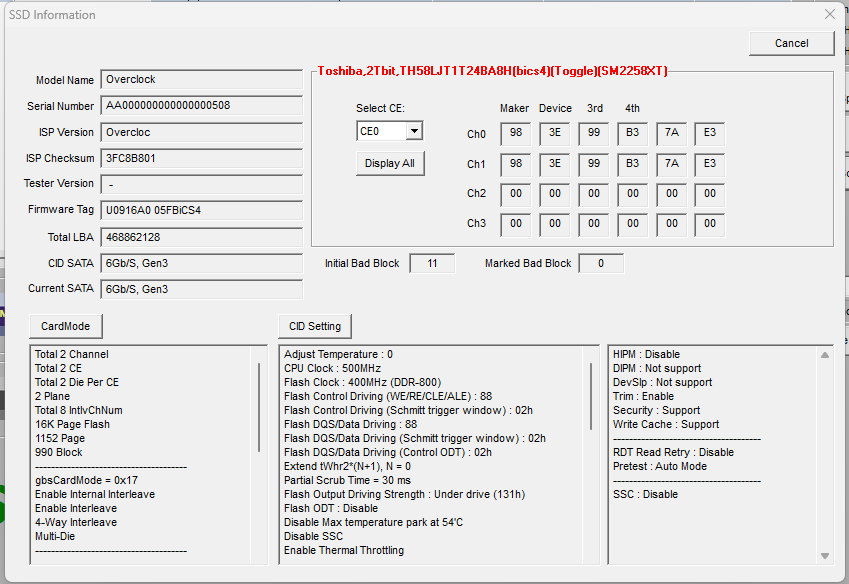

Regarding its storage, the 240GB SSD has 1 Nand flash chip, the “TH58LJT1V24BA8H.” These are Nand chips from the Japanese manufacturer Kioxia/Toshiba, model BiCS4. In this case, the dies are 256Gb (32GiB) with 96 layers of data and a total of 109 gates, resulting in an array efficiency of 88.1%.

In this SSD, each NAND Flash has 8 dies with a density of 256Gb, totaling 256GB per NAND, resulting in a total of 240GB for the SSD. They communicate with the controller with a maximum bus speed of 193.75 MHz (387.5 MT/s), which is well below the capability of the NAND chips. Both these BiCS4 512Gb and BiCS4 256Gb dies are capable of running at 400 MHz (800 MT/s).

There are several reasons for running at such a low speed. It could be due to the manufacturer choosing to reduce power consumption and heat. Alternatively, this batch of NAND Flash might not pass Kioxia’s Quality Control at higher frequencies, and as a result, it is sold at a lower cost. There is also a possibility of lower endurance, contributing to a lower cost for SSDs like this one.

SOFTWARES USED FOR OVERCLOCKING

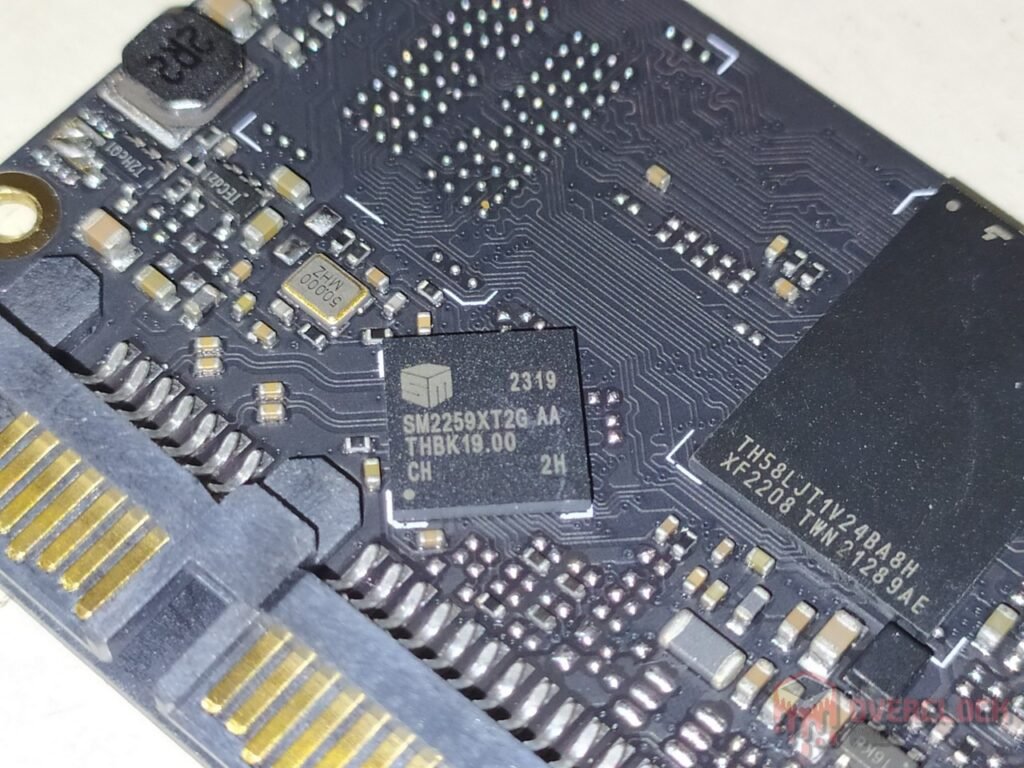

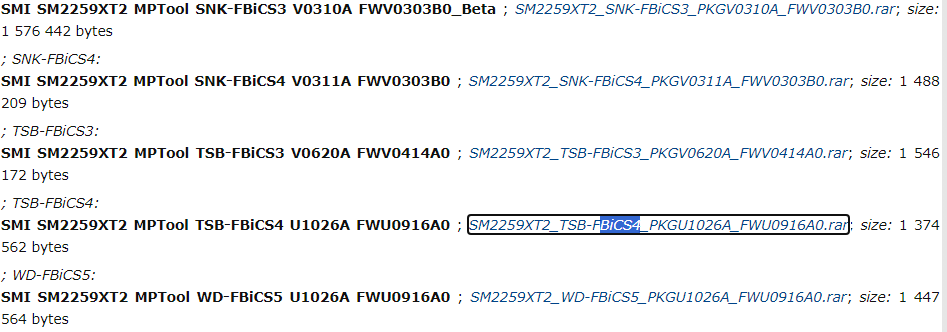

Since this is a Silicon Motion controller, we will use a mass production tool from them, known as MPtools, which is used for this same purpose, the mass production of SSDs on a production line.

It is worth noting that these softwares are NOT provided by the manufacturers but are LEAKED by individuals with access and posted on Russian or Chinese forums.

For this project, we will use the “SMI SM2259XT2 MPTool TSB-FBiCS4 U1026A FWU0916A0,” which needs to be compatible with both the controller and the NAND Flash, and this tool allows us to do that.

Right after downloading the software, we need to start making modifications, which might seem simple at first glance since we have the “Flash Clock” and “CPU Clock” sections in the lower-left corner. However, we have many parameters that we need to adjust for fine-tuning, and to ensure it works without any issues, such as:

- Flash IO Driving with it’s sub-divisons

- Flash Control Driving

- Flash DQS/Data Driving

Where these two parameters use hexadecimal values, and they must be changed according to the desired speed we will configure for the SSD.

We also have other parameters to pay attention to as well.

- Control ODT (On-die Termination)

- Flash ODT (On-die Termination)

- Schmitt Window Trigger

I won’t go into what these are in this article to keep it from being too long and boring for readers since they are more advanced topics related to signal integrity for both the transmitter and receiver, among various other parameters.

OVERCLOCKING DONE, NOW TO THE BENCHMARKS!

In a way that the SSD remains stable during the tests, I managed to stabilize it with a controller frequency of 500 MHz, which was an overclock of more than 17%. Meanwhile, in the NAND Flash, I was able to make them run for a while at 800 MT/s, which is more than double. I changed the name of the SSD to “Overclocking” since the SSD is mine, and I have already voided the warranty and applied my custom firmware.

BANCADA DE TESTES

- Operating System: Windows 11 Pro 64-bit (Build: 22H2)

- Processor: Intel Core i7 13700K (5.7GHz all core) (E-cores and Hyper-threading disabled)

- RAM: 2 × 16 GB DDR4-3200MHz CL-16 Netac (with XMP)

- Motherboard: MSI Z790-P PRO WIFI D4 (Bios Ver.: 7E06v18)

- Graphics Card: RTX 4060 Galax 1-Click OC (Drivers: 537.xx)

- Storage (OS): Solidigm P44 Pro 2TB SSD (Firmware: 001C)

- Tested SSD: “Overclock” SSD (Firmware: My custom Firmware)

- Intel Z790 Chipset Driver Version: 10.1.19376.8374.

- Windows: Indexing disabled to not affect test results.

- Windows: Windows updates disabled to not affect test results.

- Windows: Most background-running Windows applications disabled.

- Windows Boot Test: Clean image with only drivers and all updates.

- pSLC Cache Test: The SSD is cooled by fans to avoid thermal throttling, affecting the results.

- Windows: Anti-virus disabled to reduce variation in each round.

- Tested SSDs: Used as a secondary disk, with 0% of space being used, and other tests with 50% of space used to represent a realistic scenario.

- Quarch PPM QTL1999 – Power consumption test: conducted with 3 parameters, in idle where the disk is left as secondary, and after some time in idle, recording is performed for 1 hour, and the average is taken.

CONTRIBUTION TO PROJECTS LIKE THIS IN THE FUTURE

If you enjoyed this article and would like to see more articles like this, I’ll leave a link below where you can contribute directly. In the future, I plan to bring a comparison showing the difference in SLC cache sizes, transforming a QLC or TLC SSD into SLC, among various other topics.

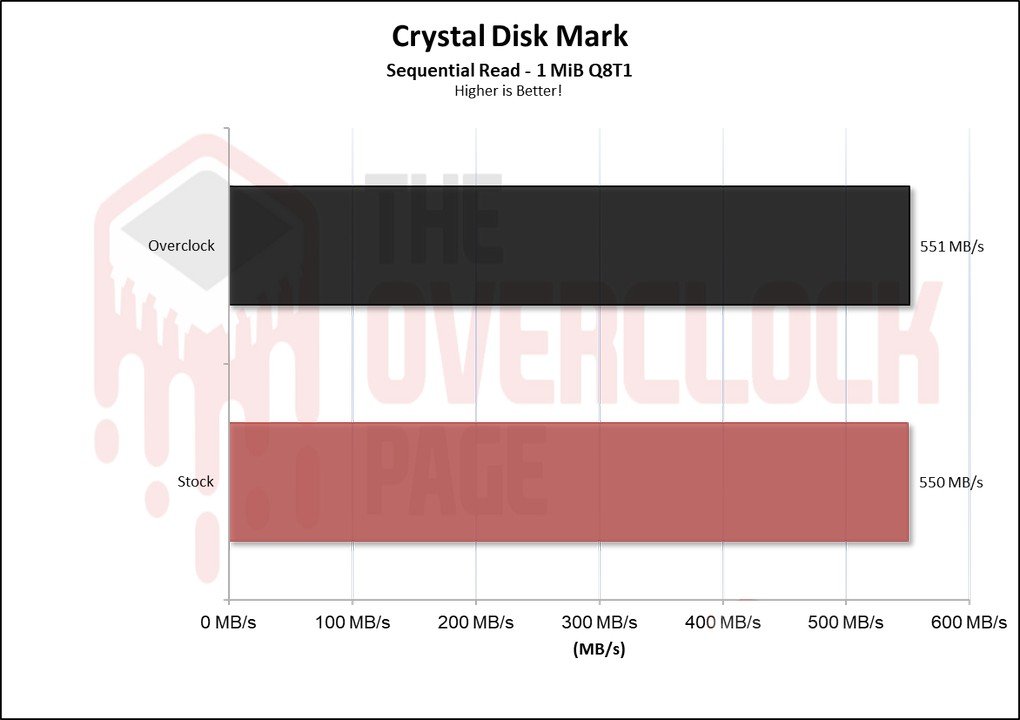

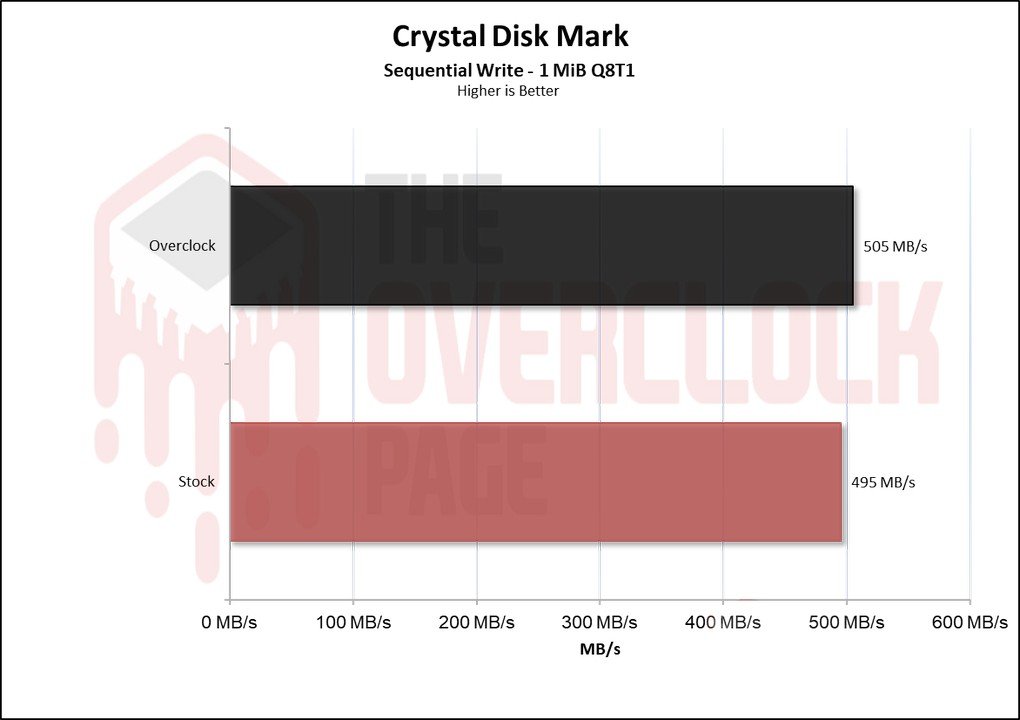

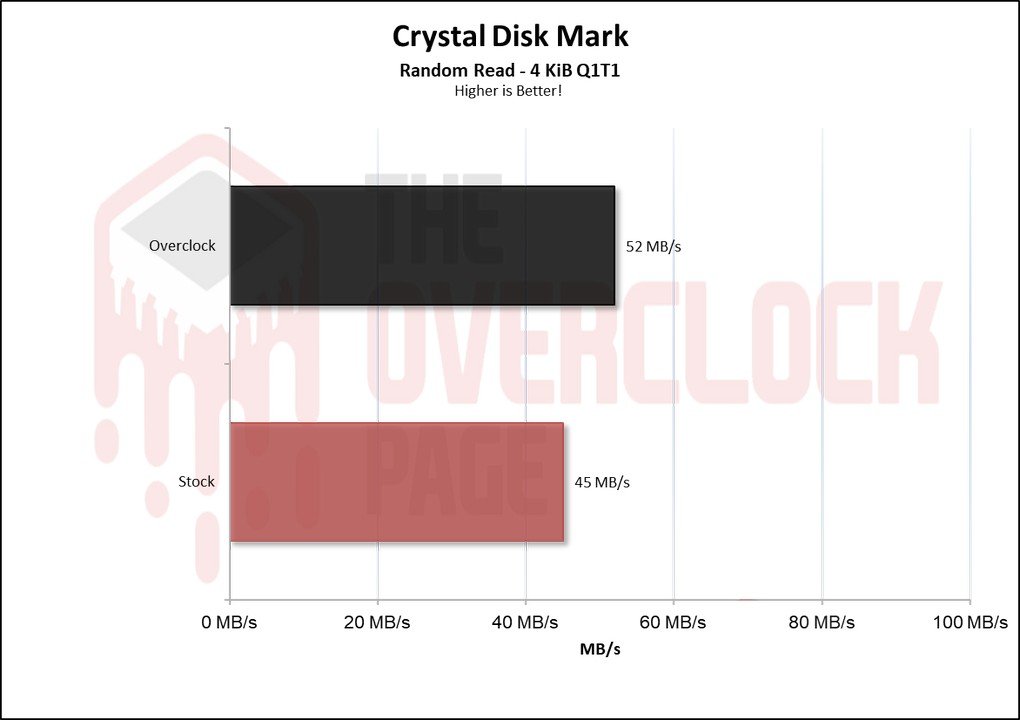

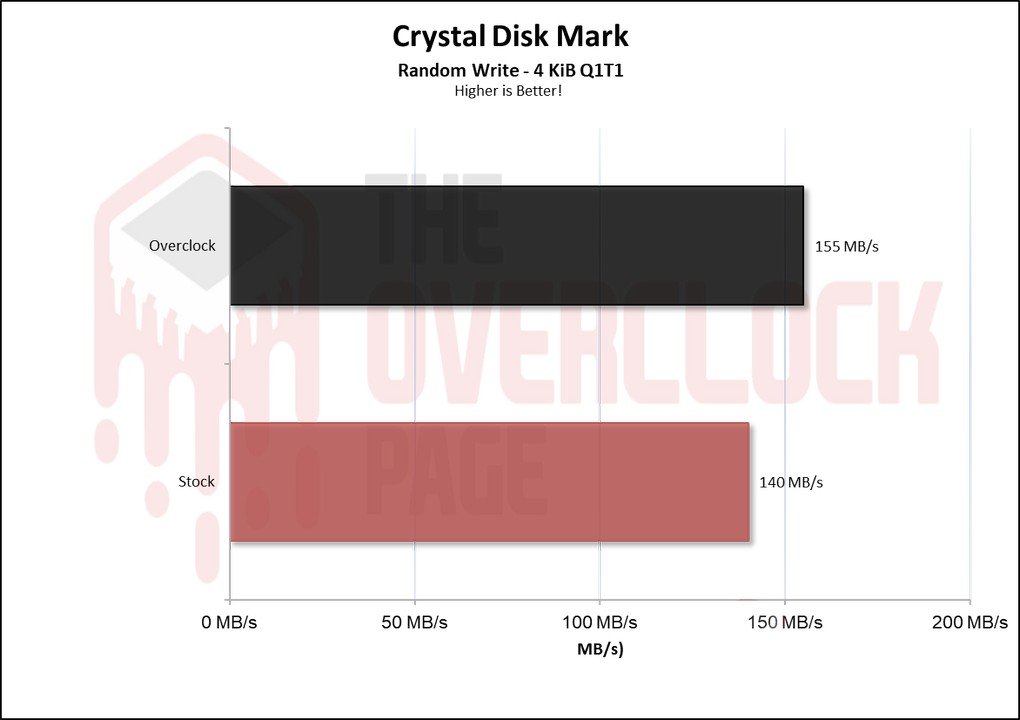

CRYSTALDISKMARK

We conducted synthetic sequential and random tests with the following configurations:

Sequential: 2x 1 GiB (Blocks 1 MiB) 8 Queues 1 Thread

Random: 2x 1 GiB (Blocks 4 KiB) 1 Queue 1/2/4/8/16 Threads

We observe that in the sequential read and write scenario, there was no difference because the SSD was already limited by the SATA bus when using the SLC Cache technique. Therefore, I did not expect to see any noticeable difference here.

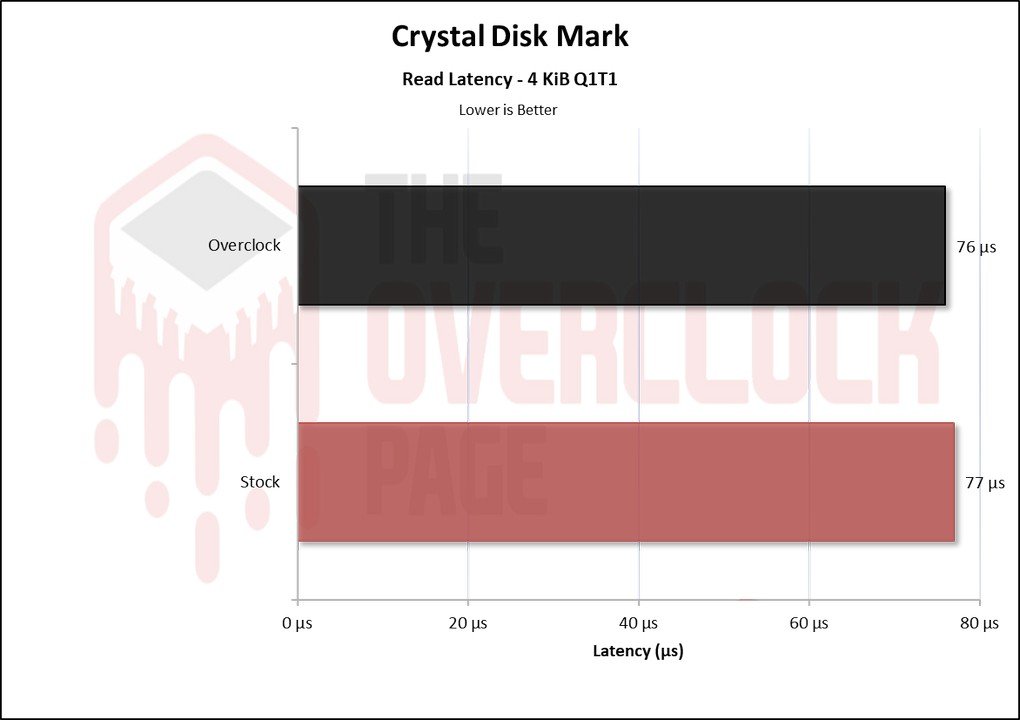

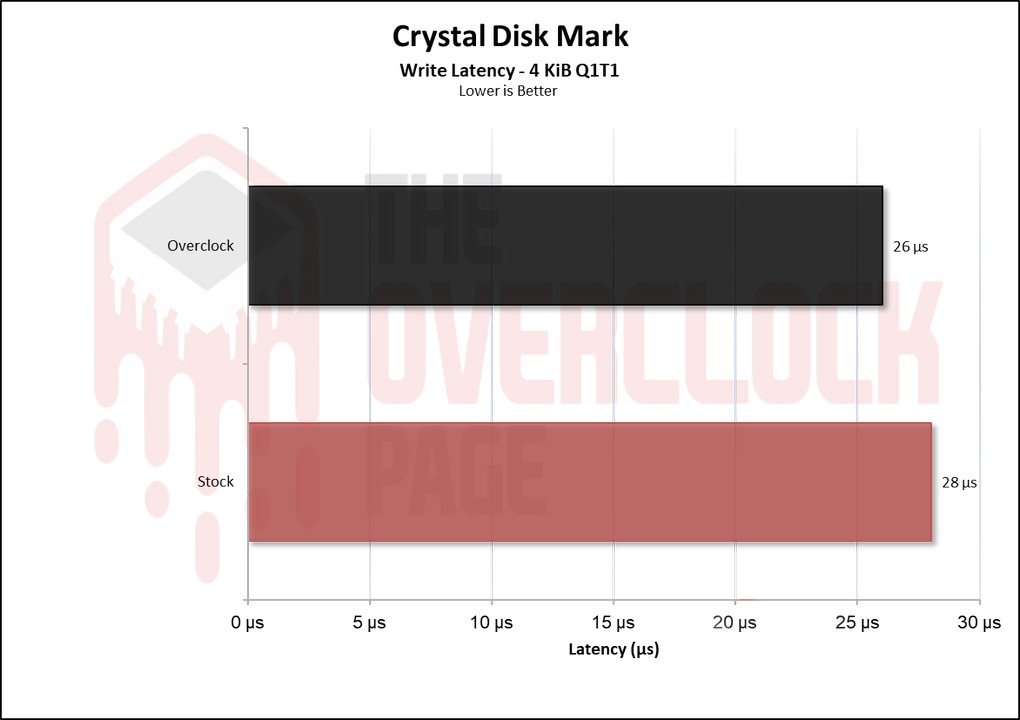

In terms of latency, there was a slight decrease when we overclocked, which was an interesting point.

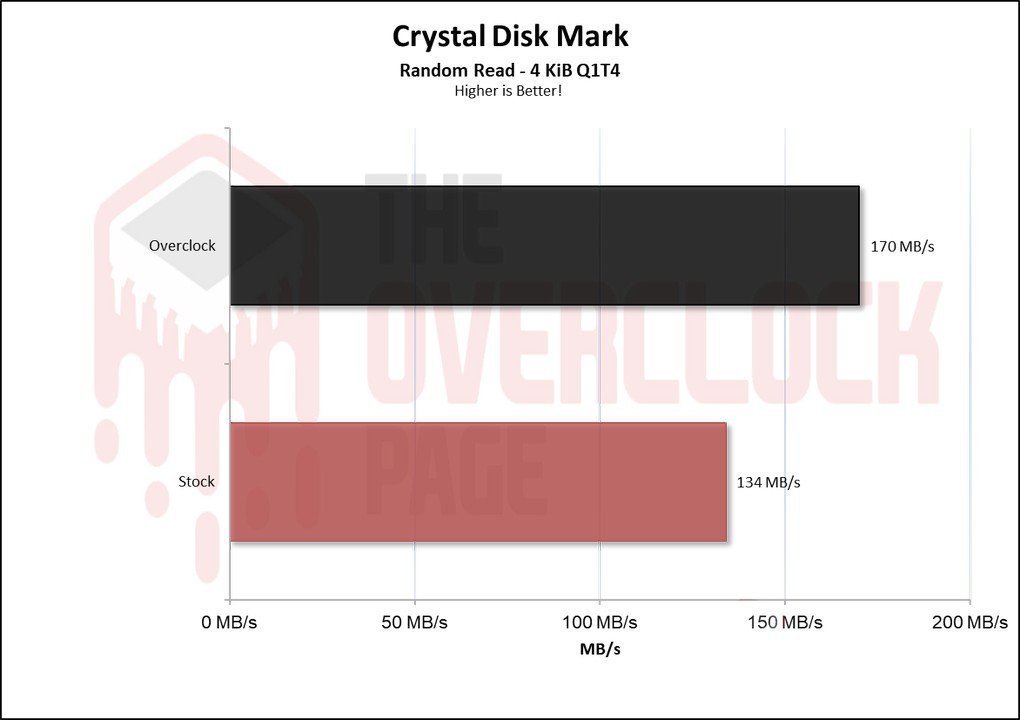

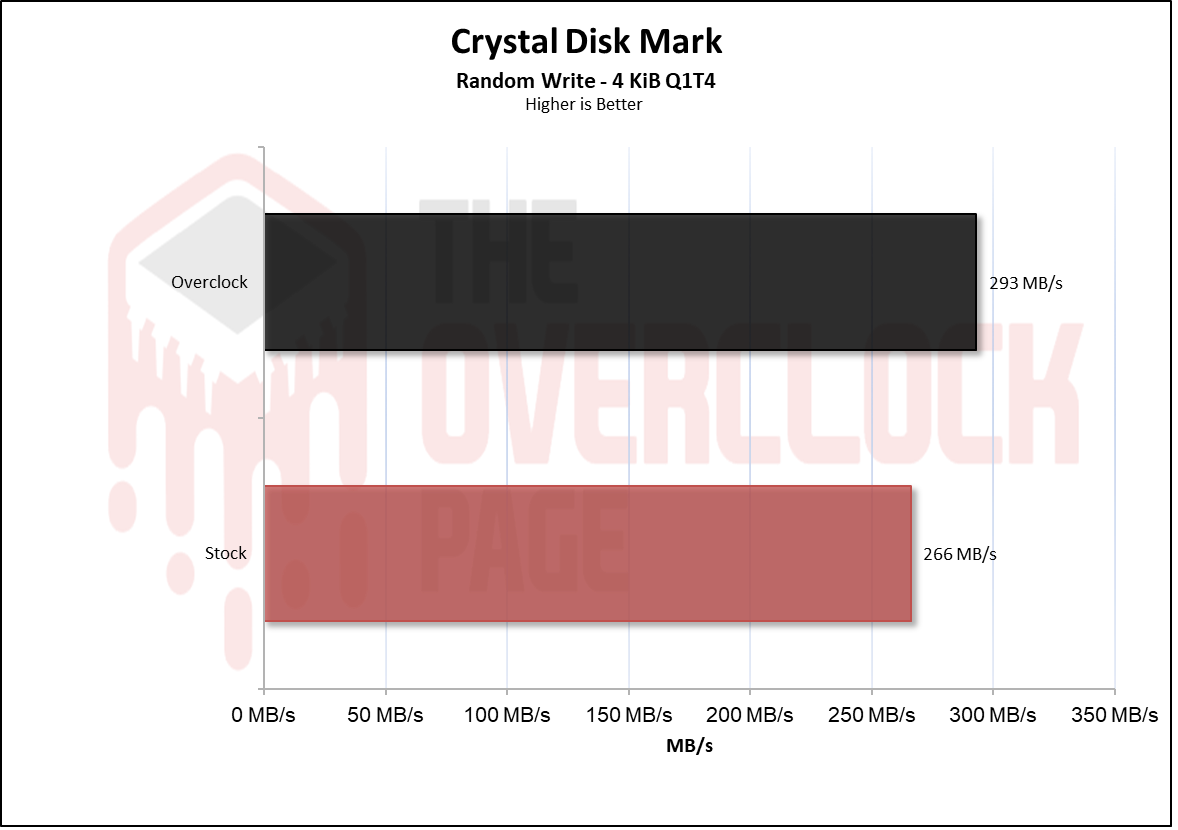

And it is in these types of scenarios that a higher bandwidth in the NAND Flash contributes to an SSD. We can see that it had a more significant increase in both read and write operations.

The same occurs at QD1, although it was to a slightly lesser extent than at Queue Depth 4.

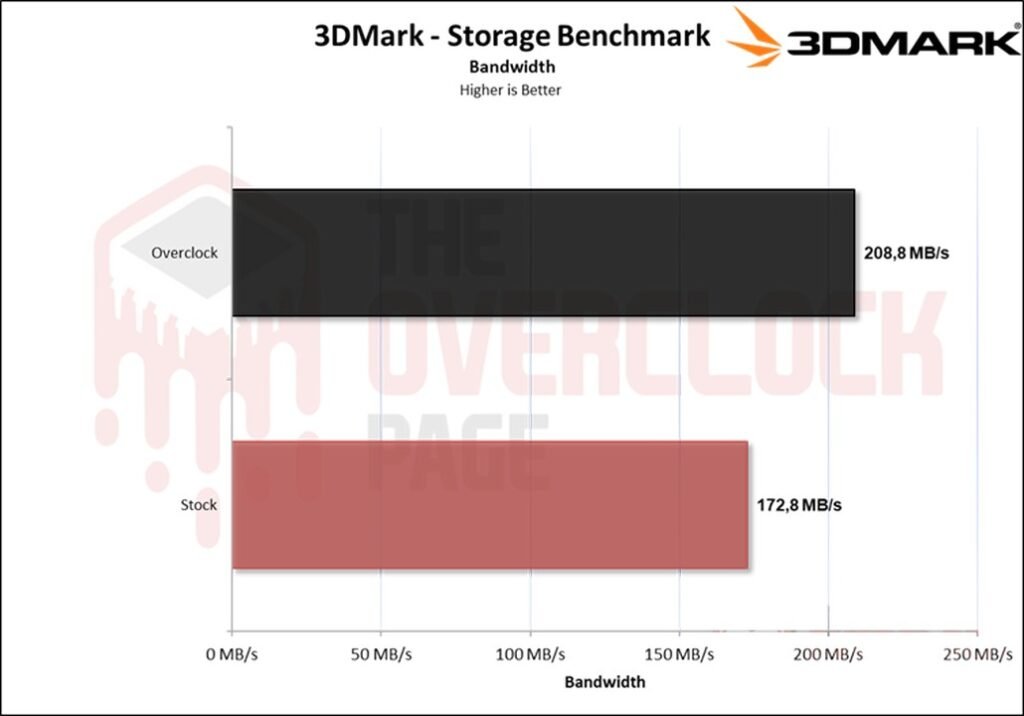

3DMark – Storage Benchmark

On this benchmark, various storage-related tests are conducted, including game loading tests for titles like Call of Duty Black Ops 4, Overwatch, recording and streaming with OBS at 1080p 60 FPS, game installations, and file transfers of game folders.

In this benchmark with a greater focus on casual environments, we can see that even here, there is a noticeable difference in performance. Throughout the analysis, it won’t make games load faster, but it significantly increased bandwidth and reduced latency, ultimately resulting in a higher score.

PCMARK 10 – FULL SYSTEM DRIVE BENCHMARK

“In this test, the Storage Test tool and the Full System Drive Benchmark test were used, which perform light and heavy tests on the SSD.”

Among these traces, we can observe tests such as:

- Boot Windows 10

- Adobe After Effects: Start the application until it is ready for use

- Adobe Illustrator: Start the application until it is ready for use

- Adobe Premiere Pro: Start the application until it is ready for use

- Adobe Lightroom: Start the application until it is ready for use

- Adobe Photoshop: Start the application until it is ready for use

- Battlefield V: Loading time to the start menu

- Call of Duty Black Ops 4: Loading time to the start menu

- Overwatch: Loading time to the start menu

- Using Adobe After Effects

- Using Microsoft Excel

- Using Adobe Illustrator

- Using Adobe InDesign

- Using Microsoft PowerPoint

- Using Adobe Photoshop (Intensive use)

- Using Adobe Photoshop (Lighter use)

- Copying 4 ISO files, 20GB in total, from a secondary disk (Write test)

- Performing the copy of the ISO file (Read-write test)

- Copying the ISO file to a secondary disk (Read)

- Copying 339 JPEG files (Photos) to the tested disk (Write)

- Creating copies of these JPEG files (Read-write)

- Copying 339 JPEG files (Photos) to another disk (Read)

“In this scenario, which is a practical benchmark with a slightly greater focus on writing than 3DMark, we see again that the performance has increase.

PROJECT – Adobe Premiere Pro 2021

Next, we use Adobe Premiere to measure the average time it takes to open a project of around 16.5GB with a 4K resolution, 120Mbps bitrate, full of effects until it was ready for editing. It is important to note that the tested SSD is always used as a secondary drive without the operating system installed, as this could affect the result, leading to inconsistencies.

Here, it was not possible to notice a difference, so we consider it a technical tie.

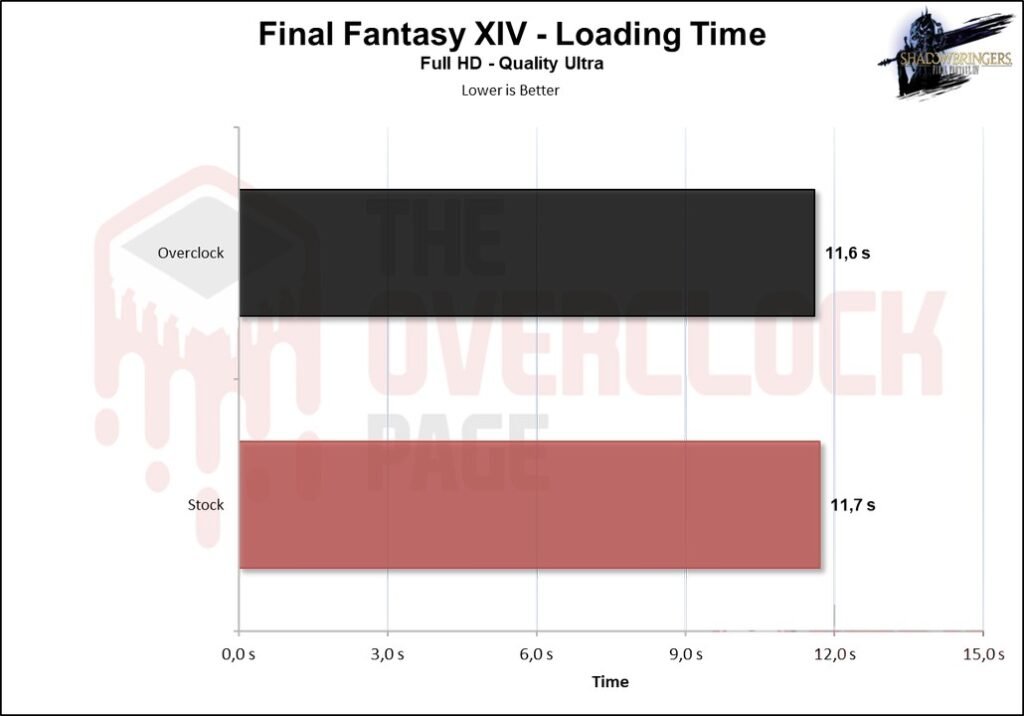

GAME LOADING TIMES

“We compared multiple SSDs and an HDD using the Final Fantasy XIV benchmark with the campaign mode open.”

The same happens in game loading scenarios where the limitation is how the game loads textures and necessary information.

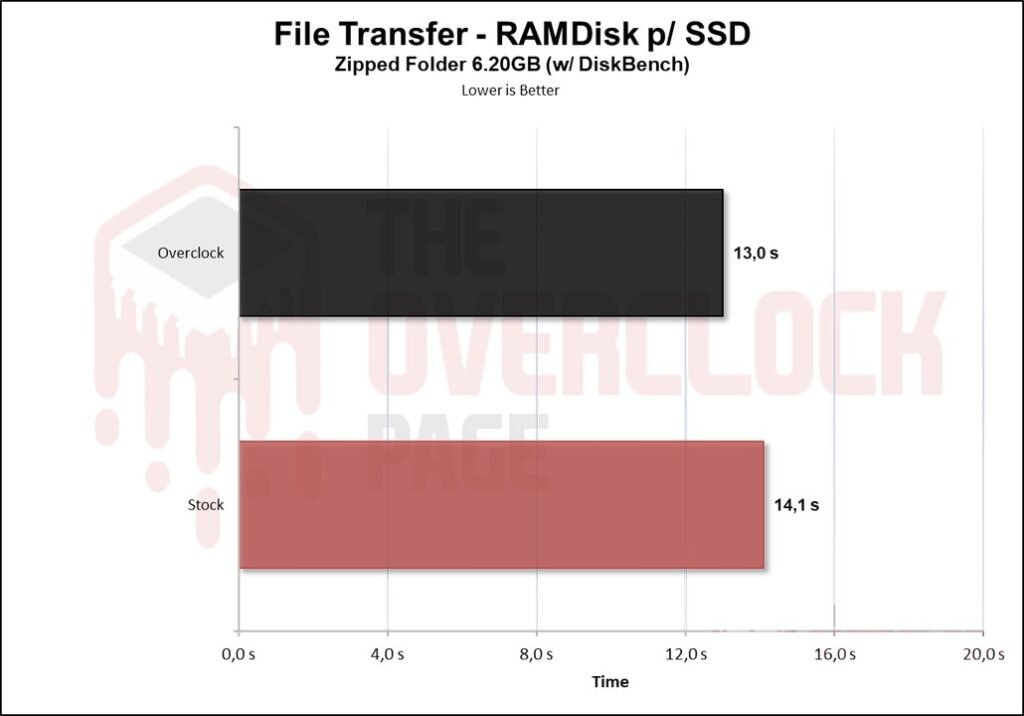

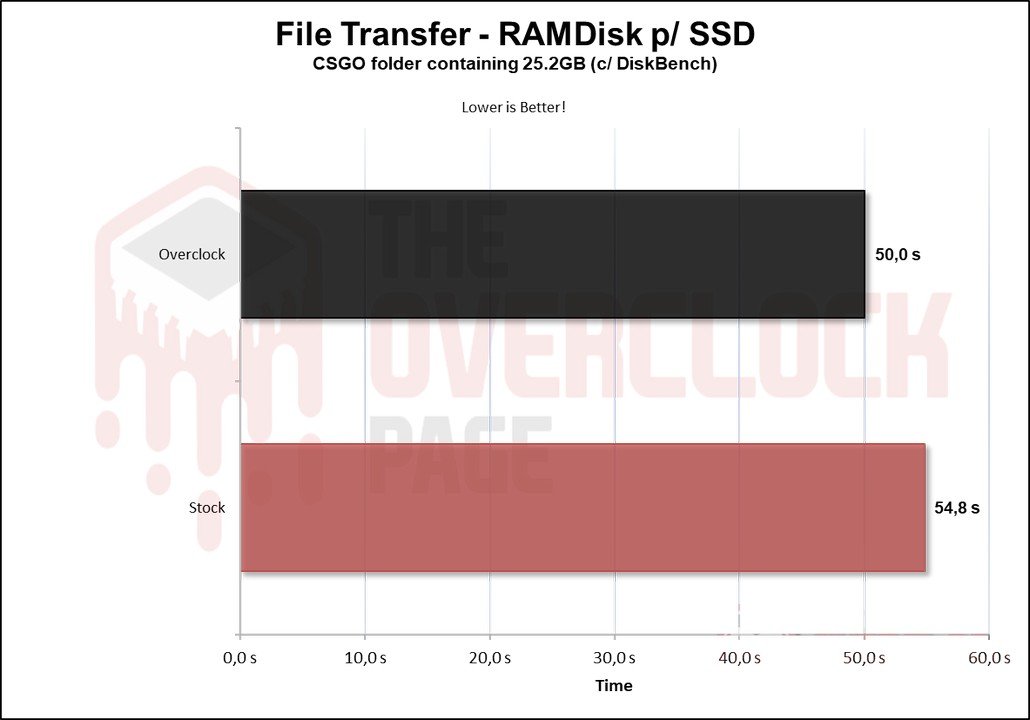

FILE COPY BENCHMARKS

In this test, the ISO files and CSGO files were copied from a RAM Disk to the SSD to see how it performs. The Windows 10 21H1 ISO file of 6.25GB (1 file) and the CSGO installation folder of 25.2GB were used.

In a more realistic test like this, it was possible to gain a 1-second improvement in the transfer of small files.

And when using larger folders, the difference increases, but not to the extent of being a landslide.

TEMPERATURE STRESS TEST

In this part of the analysis, we will observe the temperature of the SSD during a stress test, where the SSD receives continuous file transfers, to determine if there was any thermal throttling with its internal components that could lead to bottlenecks or performance loss.

We can see that the SSD heats up more due to overclocking, but we should note something: at stock settings, it always stays “locked” at 40ºC. This is because the manufacturer configured the SSD in this way, and to prove it, take a look at the image below.

I don’t believe it was an interesting choice. And indeed, it doesn’t go much above that, with the SSD configured to undergo thermal throttling at 54ºC.

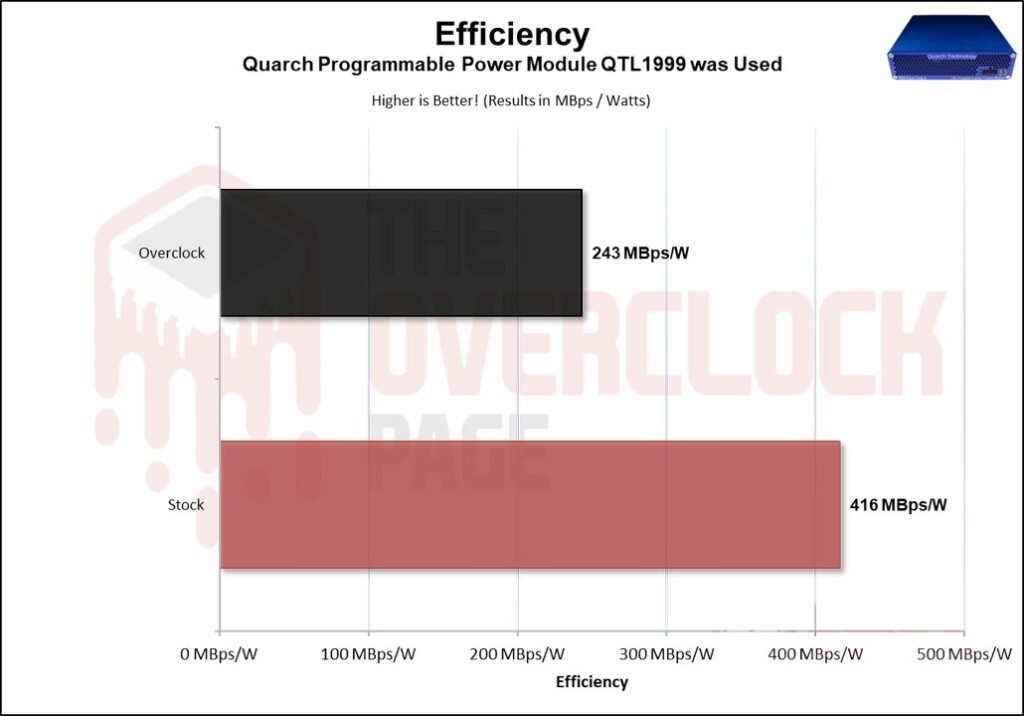

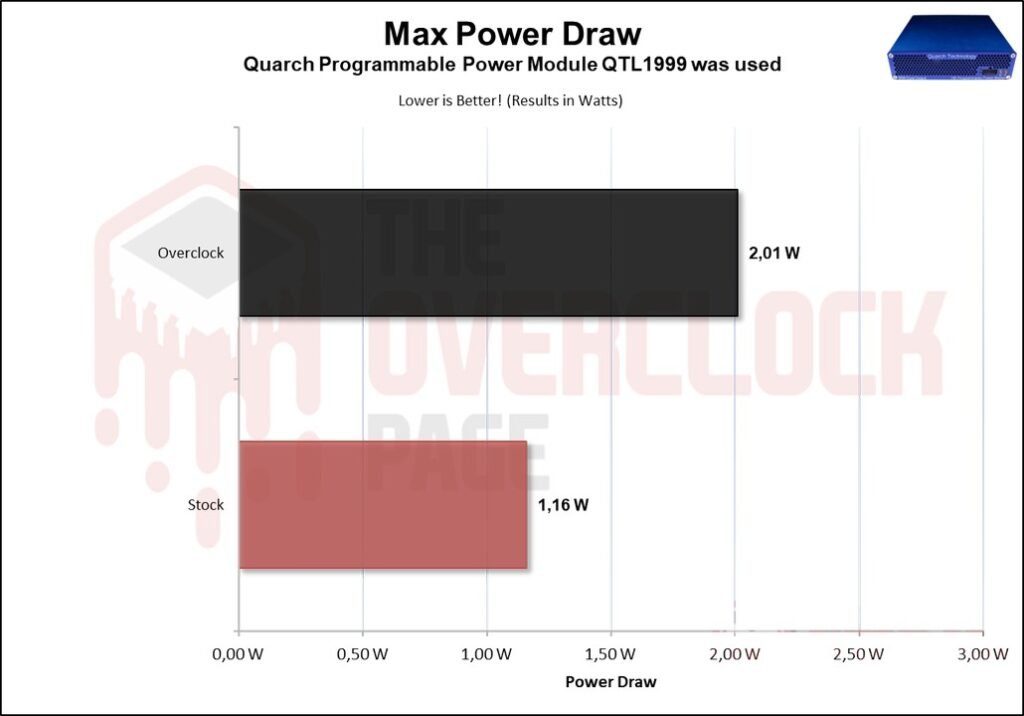

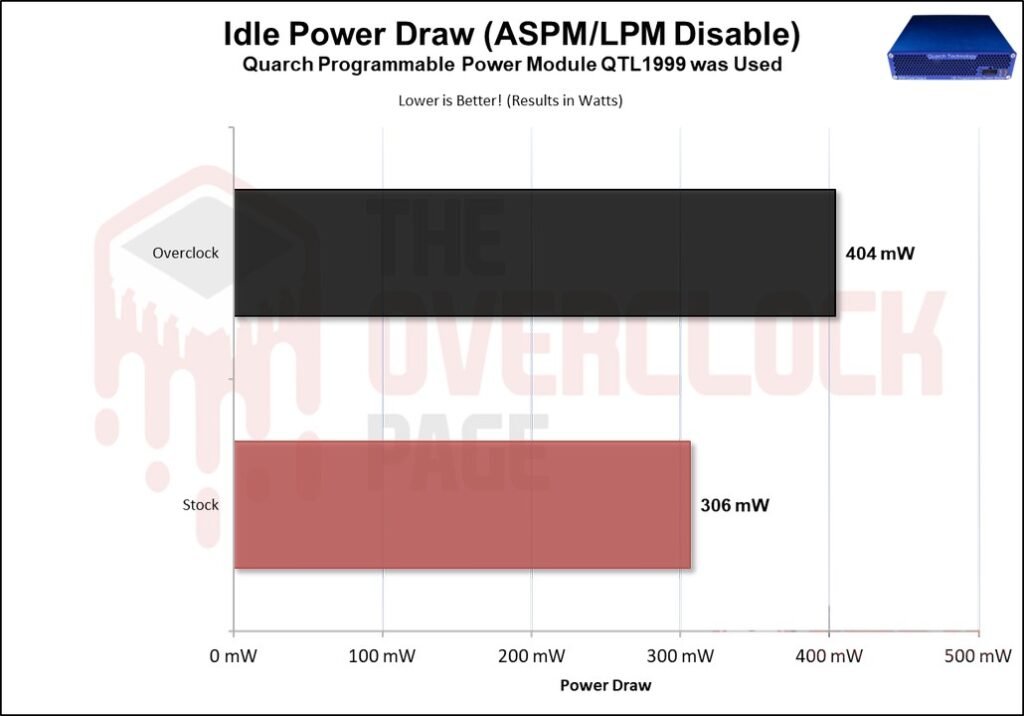

POWER CONSUMPTION AND EFFICIENCY

SSDs, like many other components in our system, have a certain power consumption. The most efficient ones can perform tasks quickly with relatively low power consumption, allowing them to transition back to idle power states where consumption tends to be lower.

In this section of the analysis, we will use the Quarch Programmable Power Module that Quarch Solutions provided (pictured above) to conduct tests and assess the SSD’s efficiency. In this methodology, three tests will be performed: the maximum power consumption of the SSD, an average in practical and casual scenarios, and power consumption in idle.

This set of tests, especially those related to efficiency and idle power consumption, is crucial for users who intend to use SSDs in laptops. Since SSDs spend the majority of their time in low-power states (Idle), this information is essential for battery savings.

Regarding its efficiency, due to the higher power draw, it had decreased when compare to stock operations.

We can see that applying this overclocking nearly doubled its power consumption, which was quite interesting to observe. However, it penalizes efficiency significantly. For this reason, among those mentioned earlier, the manufacturer may have configured the SSD with lower frequencies.

Its average power consumption also increased considerably, even though its bandwidth increased only slightly.

Lastly, and most importantly, the Idle test, which is the scenario where the vast majority of SSDs are in everyday use. We observe that its idle power consumption has also increased considerably, by more than 30%.

Well, guys, the bad news is that the SSD ultimately died, however I managed to complete the entire test bench; it died during a write test I was conducting to assess the average WAF it was presenting.

Well, that’s it for today, folks. I hope you enjoyed it. And stay tuned because soon I’ll be writing an article on turning a QLC or TLC SSD into SLC mode, making it super durable and much faster, greatly extending its lifespan.