Build log – Tuning a Sugo SG13 SFF PC with 3D Printing and High-End GPU!

Compact PCs, also known as Small Form Factor (SFF), have never been more popular, with a variety of manufacturers—both established and emerging—offering increasingly sophisticated cases. Additionally, companies like NVIDIA are investing in the SFF Ready program for their GPUs. That said, since 2021, we’ve had one of these compact machines to call our own, which has undergone several modifications over time.

In its latest iteration, the RX 6700 XT was integrated into a custom water cooling setup with homemade heatsinks on the memory and VRM. Additionally, the front of the case underwent some modifications due to one mounting pin breaking and the other three not being in great condition, which caused me some concern.

Despite the RX 6700 XT being quite robust, it was struggling to handle a 4K TV. The issue is that this case can only accommodate GPUs up to 270mm in length and with a maximum TDP of around 200W, limited by the 120mm radiator and also by myself since using two airplane-style noisy fans in a push-pull configuration isn’t a viable option.

With that in mind, I took on the challenge of installing the RX 6800 XT into this shoebox-sized case and I also decided to design and fabricate a new front panel for the case.

Throughout this article, I will detail how the GPU upgrade went. I’ll take you through every stage of developing this new front panel, from initial concept design to prototyping and final version. Additionally, I’ll share adjustments and temperature tests conducted during the process. At last I’ll outline future plans.

A Not-So-Simple GPU Upgrade

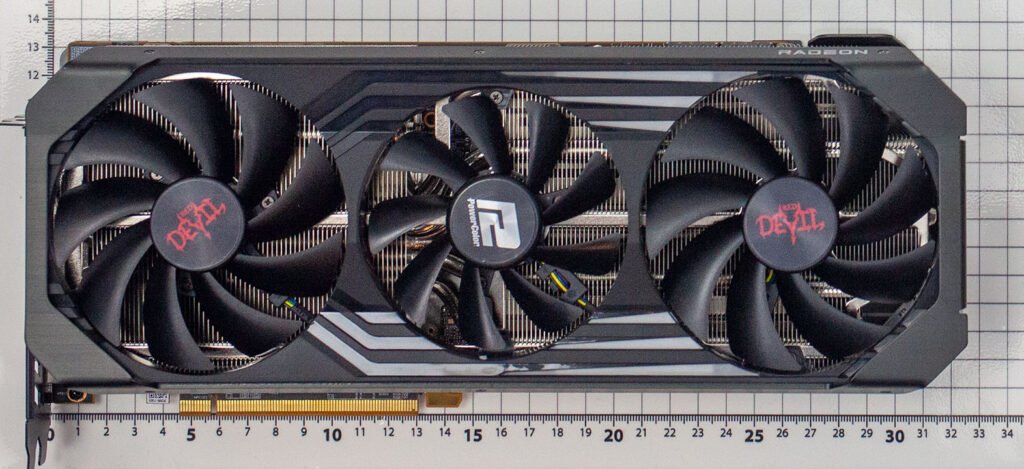

The first and most obvious challenge is that the RX 6800 XT Red Devil is a massive brick measuring 320mm x 135mm x 62mm. This means either the original cooling system or the case itself has to go, which the cooling system was the one chosen for elimination.

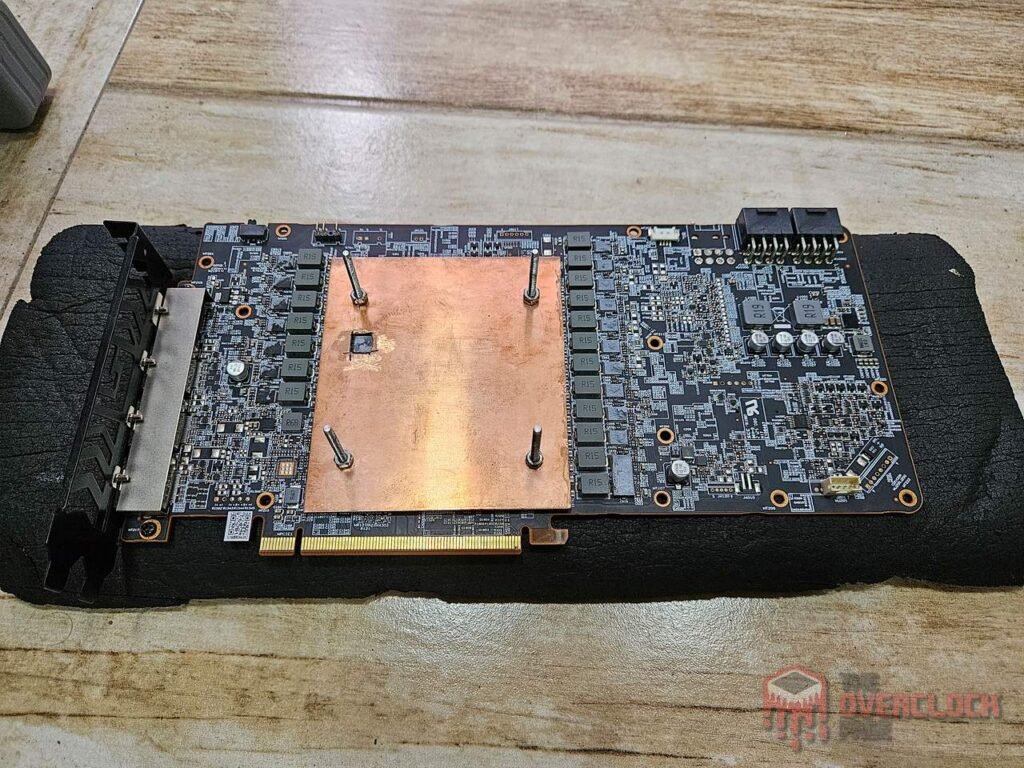

Now, if the GPU is larger than the case, how are you supposed to fit it inside? The fact of the matter is that it’s massive due to its cooling system. However, the PCB itself is slightly smaller than 270mm, so it does fit within the case.

The obvious alternative for cooling this GPU is a Water Cooler, but it’s not as straightforward as it seems. The universal block from the 6700 XT isn’t directly compatible, and even if it were, something would still be needed to cool the memory modules and VRM. To make matters worse, a full-cover block costs nearly half of the GPU’s value.

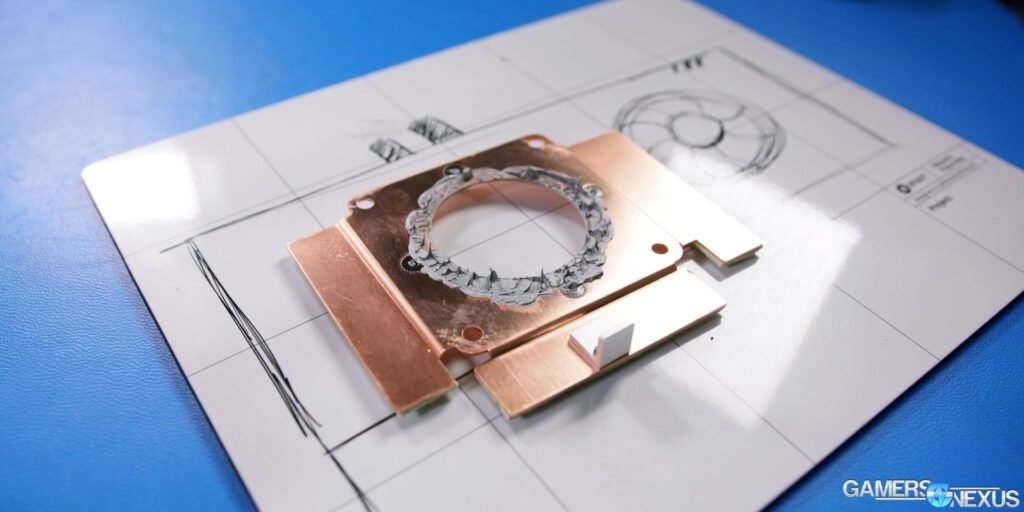

Inspiration for solving this problem came directly from the past, with EVGA’s GTX 1080 TI Hybrid. It used a sealed-loop water cooler to cool both the GPU and memory modules. They developed a copper plate that also made contact with the base of the block, resolving the issue in an extremely engineering-forward way.

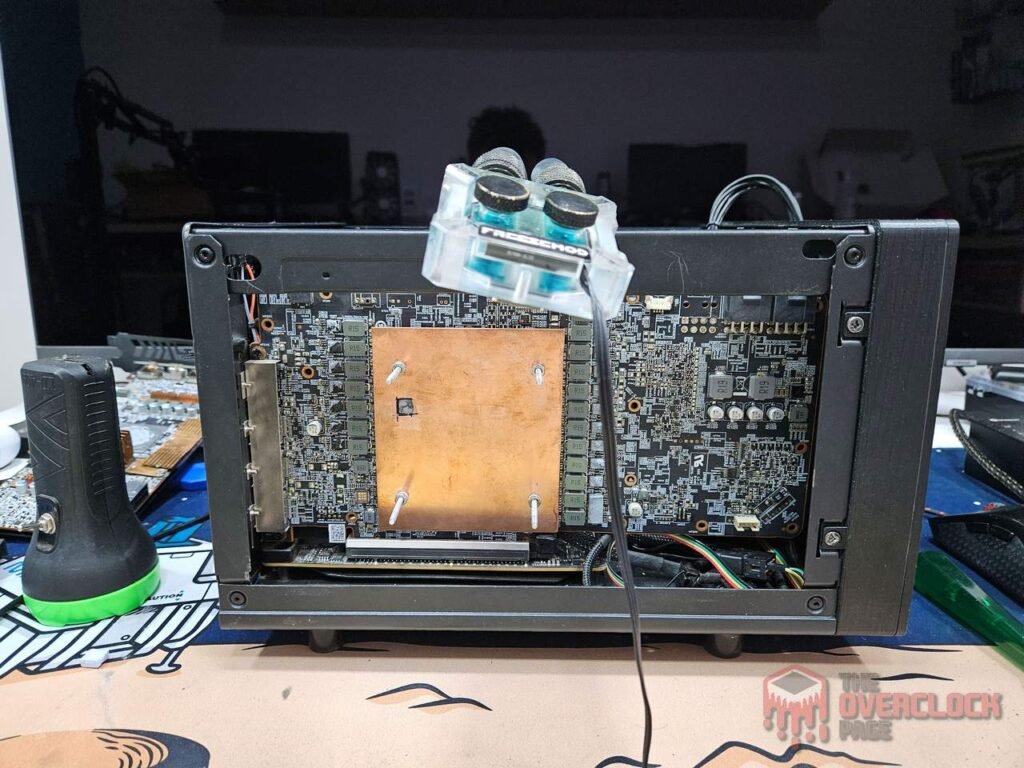

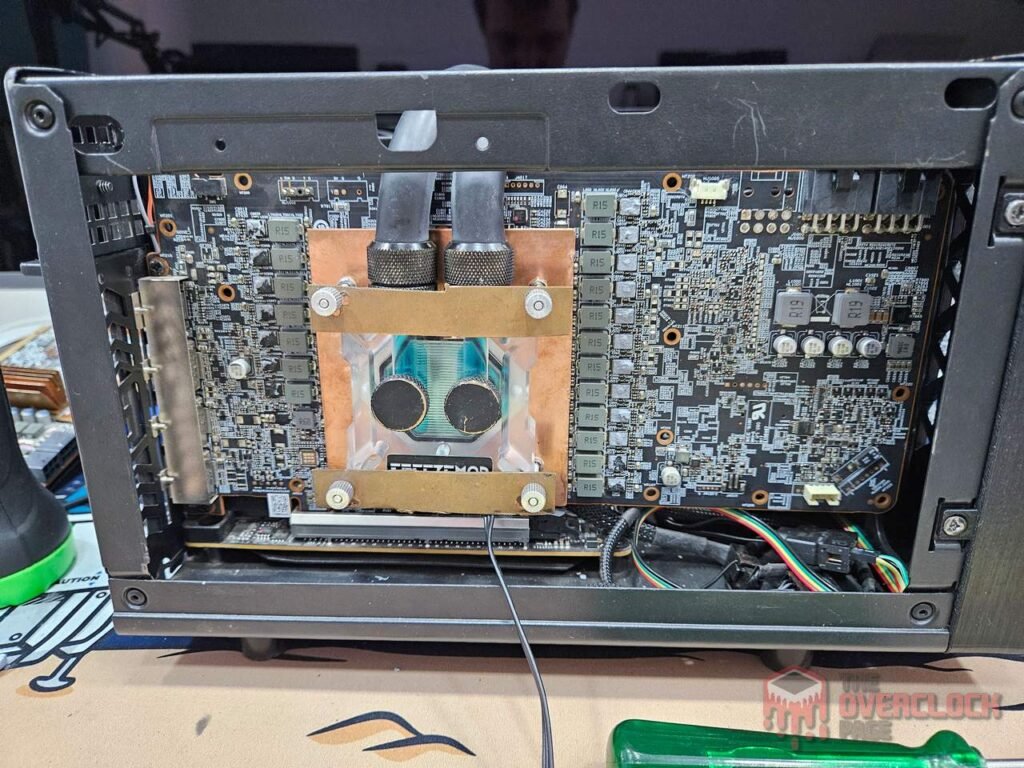

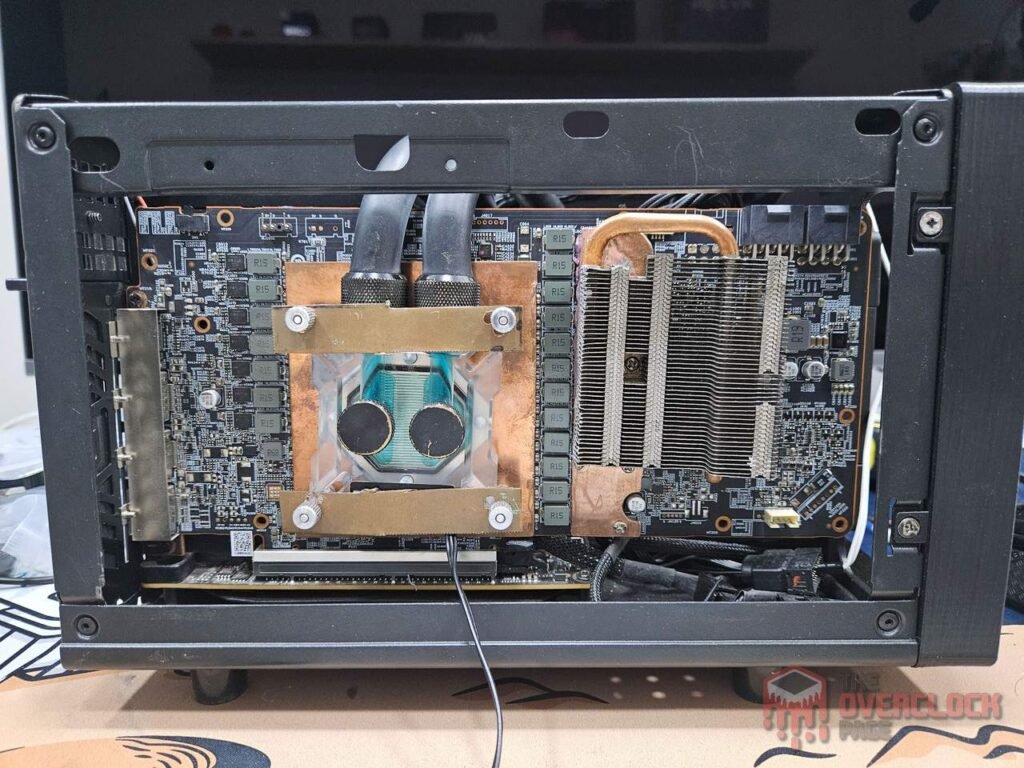

Unlike EVGA, which opted for a protrusion on the base of the block to allow direct contact with the GPU, here a 1.5mm copper plate was used to make contact both with the GPU’s die and memory chips, with the block handling heat dissipation through it.

This solution prioritized simplicity by avoiding the need to modify the block’s base with soldered protrusions and also by not requiring the cutting of the 1.5mm plate. However, it adds thermal resistance between the GPU and the block’s base, resulting in slightly higher temperatures, estimated at around +2°C compared to direct die contact.

As this is somewhat of a pioneering solution, it makes sense to conduct an initial test to verify if continuing with the development would be worthwhile. Otherwise, there is still time to reconsider the plans.

The “supports” for the block were repurposed from the reference test of the RX 6800 XT, hence the crappy appearance, but functional enough! 🙂

For this initial test, the GPU operated at standard frequency with a 980mV undervolt applied and power consumption slightly below 190W. The temperatures recorded were around 70°C, which appears satisfactory.

Since there were no heatsinks installed on the VRMs yet, I positioned two fans to blow directly onto the board as an additional precaution.

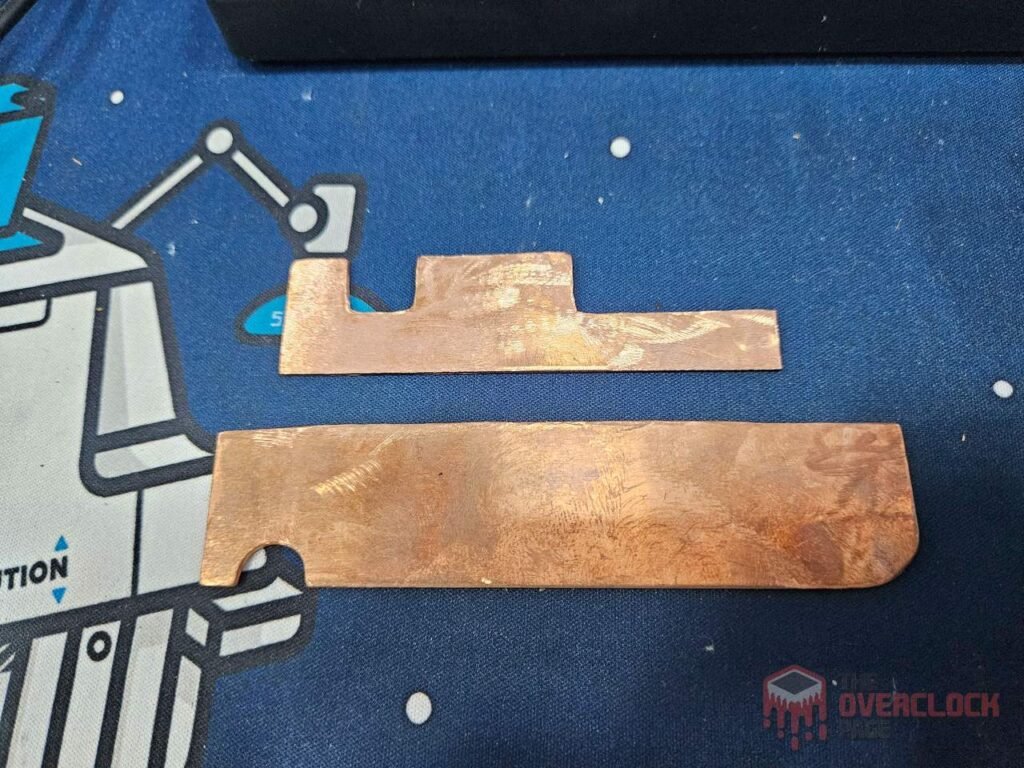

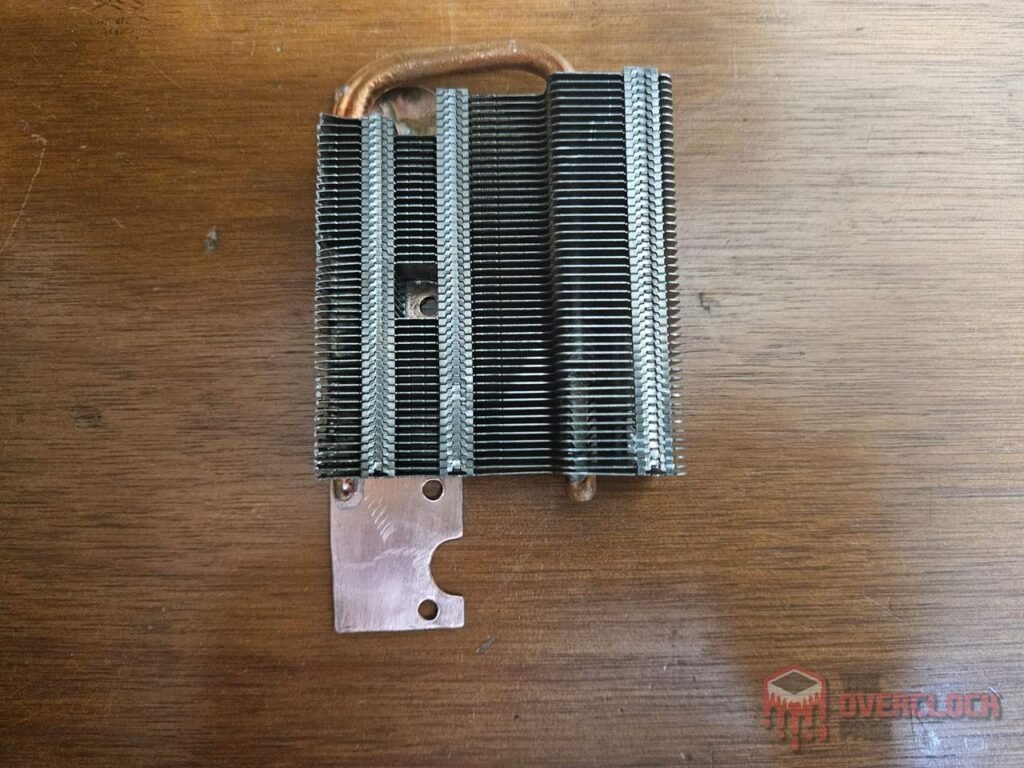

As the first test was successful, the next step was to move forward with manufacturing the bases for the VRM heat sinks using the same 1.5mm copper plate used for the GPU.

It’s worth noting that with the RX 6700 XT, I also manufactured heat sinks for memory and VRMs, but using a 0.8mm copper plate.

While the difference may seem small, it represents an increase of over 70% in the thickness of the 1.5mm copper plate compared to the 0.8mm one, which should significantly enhance the thermal capacity of the heat sinks.

It goes without saying that copper bases alone wouldn’t suffice as heatsinks, as they require fins to allow air circulation and facilitate thermal exchange through convection. Therefore, it’s essential to solder these fins onto the pieces so they can perform their intended function.

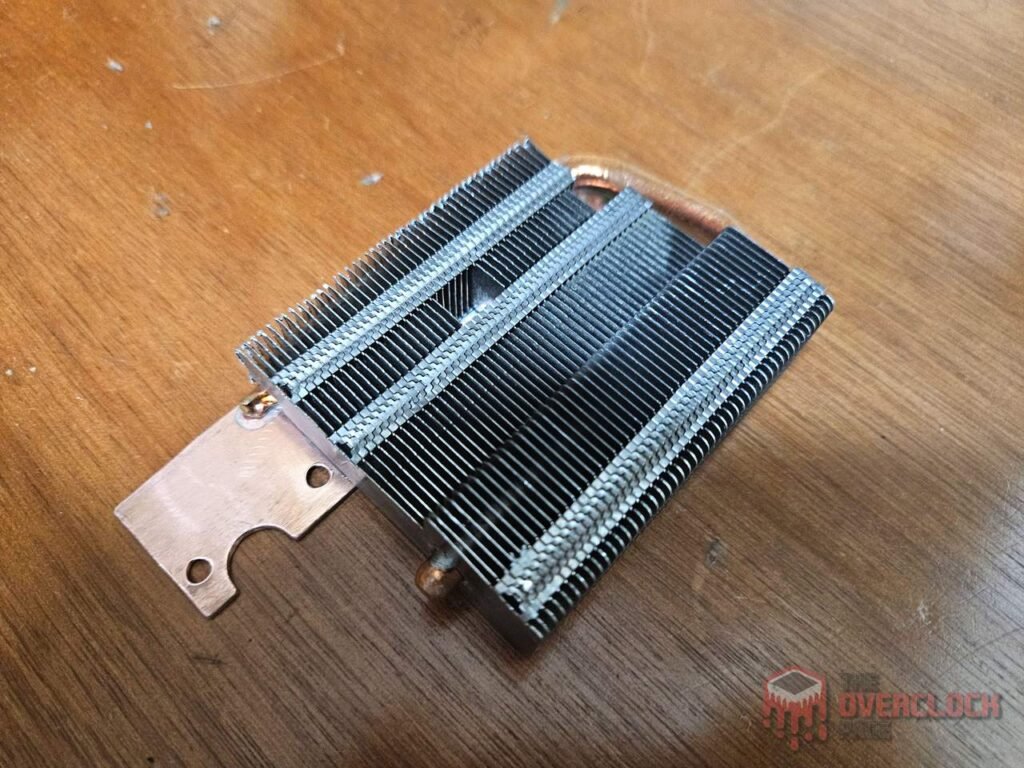

The solution involved sourcing materials from scrap. After extensive searching, I managed to find the heatsink from my old Palit RTX 580, which was clearly too large for this purpose. It required disassembly, removal of its original base, desoldering of the heatpipes, and some hacking to resizing the heat sink.

It’s important to note that soldering heatpipes requires caution. Excessive heat can impair their efficiency or cause physical damage due to internal fluid expansion. Another critical point is not exceeding the heatpipe’s thermal conductivity limits; otherwise, the final result tends to be poor. This explains why compact heatsinks with more heatpipes perform better than larger ones or those with more fans but fewer pipes.

With proper precautions in place, the soldering process was straightforward. Using low-melting-point solder and a clamp to secure the assembly, applying heat for just enough time ensured a bright metallic finish on the joints.

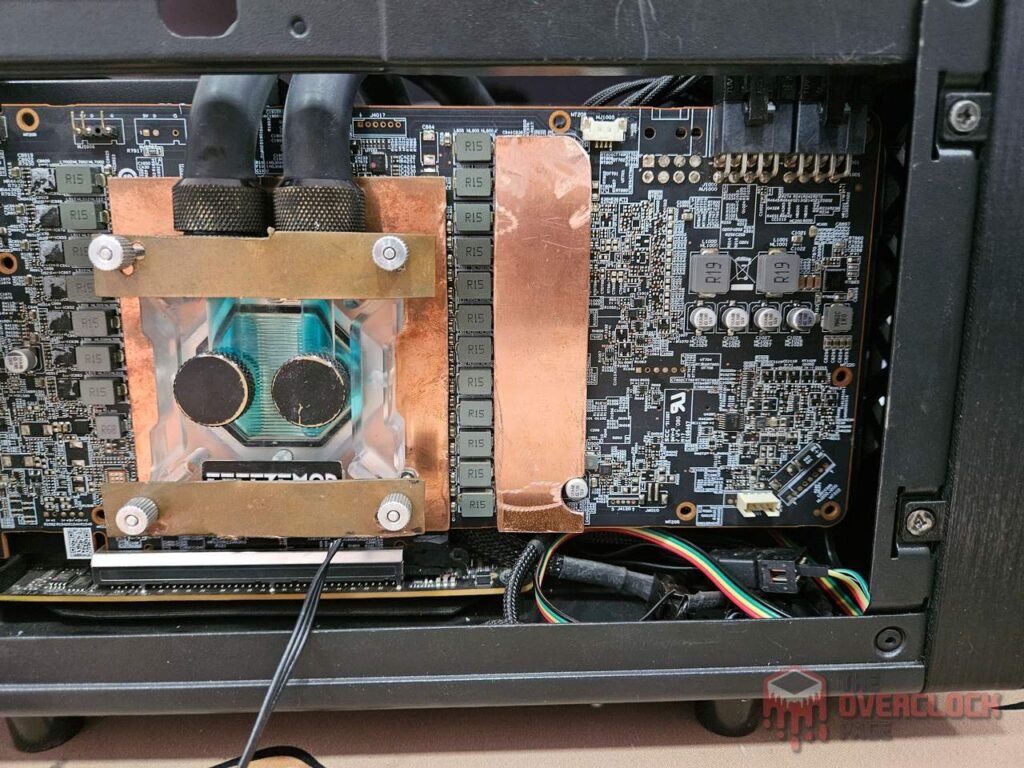

The final result can be seen in the gallery below, with a piece that perfectly serves its purpose and should be more than sufficient to keep this VRM’s temperature within acceptable levels even without active cooling.

While I aimed to create a similarly robust piece for the other side of the VRM, unfortunately, I couldn’t find any scrap that would fit in that much smaller space. As a result, it turned out to fabricate a simple and far less visually appealing piece, made by recycling the 6700 XT heatsinks, which should theoretically do its job. We’ll see how it holds up in practice.

A New Front for the Sugo!

As I mentioned before, the original front mounting tabs of the SG13 were weakened and one of them broke during the last machine move. I repaired it with epoxy resin and made another tab from what I had at home, but the main issue was that, although functional, the alignment was no longer consistent with the standard, which bothered me. Given that, why not take the opportunity to make a new front piece?

While the original design was decent, buying another front ‘from the factory’ is out of the question, even though the manufacturer does sell replacement parts. After all, I’d have to pay for international shipping and the exorbitant Brazilian import taxes, so I decided to turn to 3D printing!

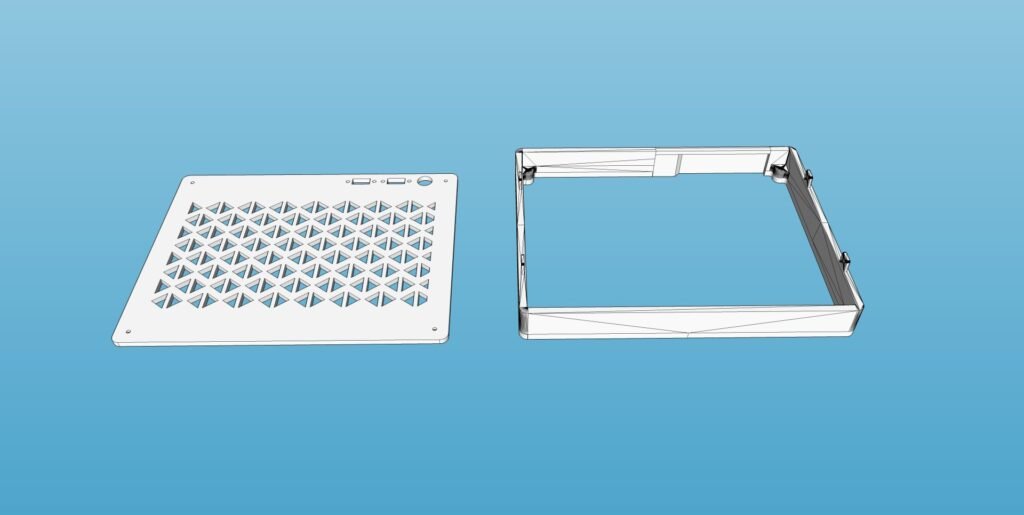

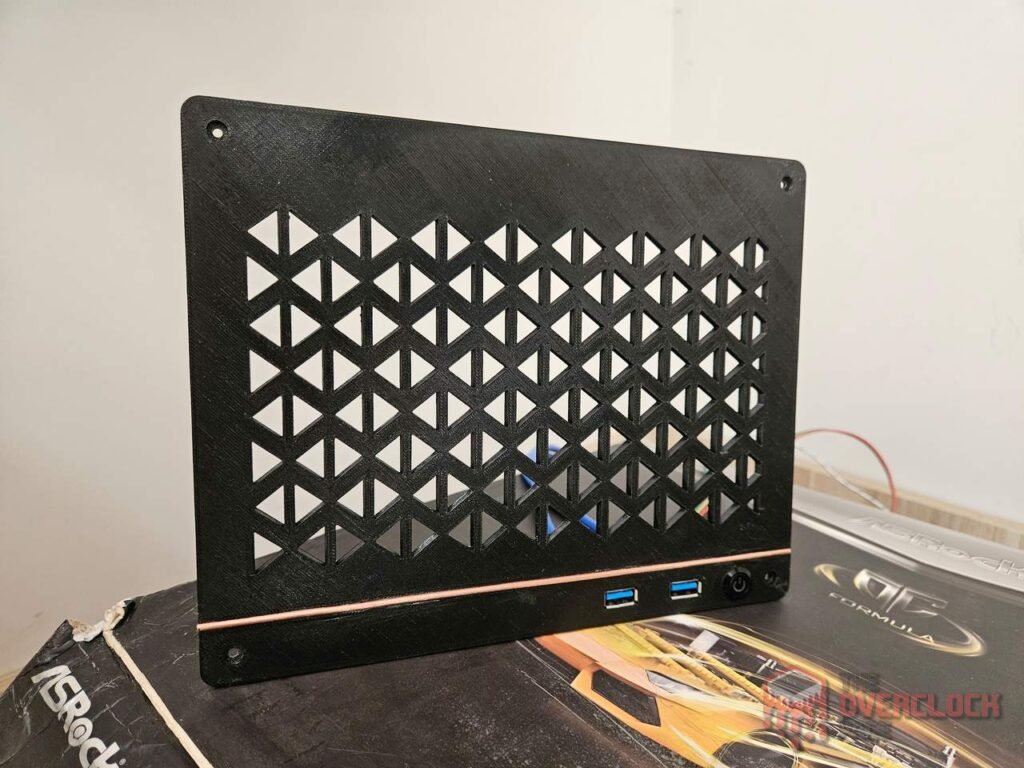

After searching online, I came across other people who had gone down this path, albeit for different reasons, and ended up finding a ready-made frame model that I only modified by adding a few millimeters in height, which would be sufficient to accommodate the slim fan without major issues. The front, on the other hand, was my own design.

The advantage of this design is that it’s very unlikely you’ll need to remove the frame from the case, thus mitigating the main problem with the original front, which was the fragility of the mounting tabs.

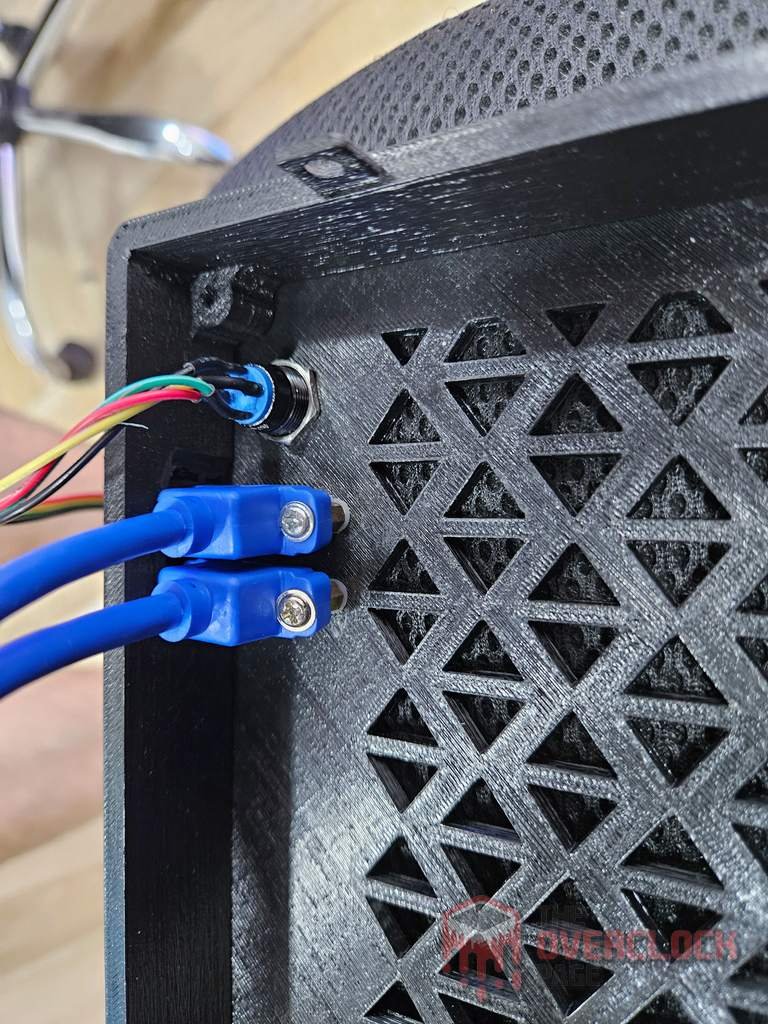

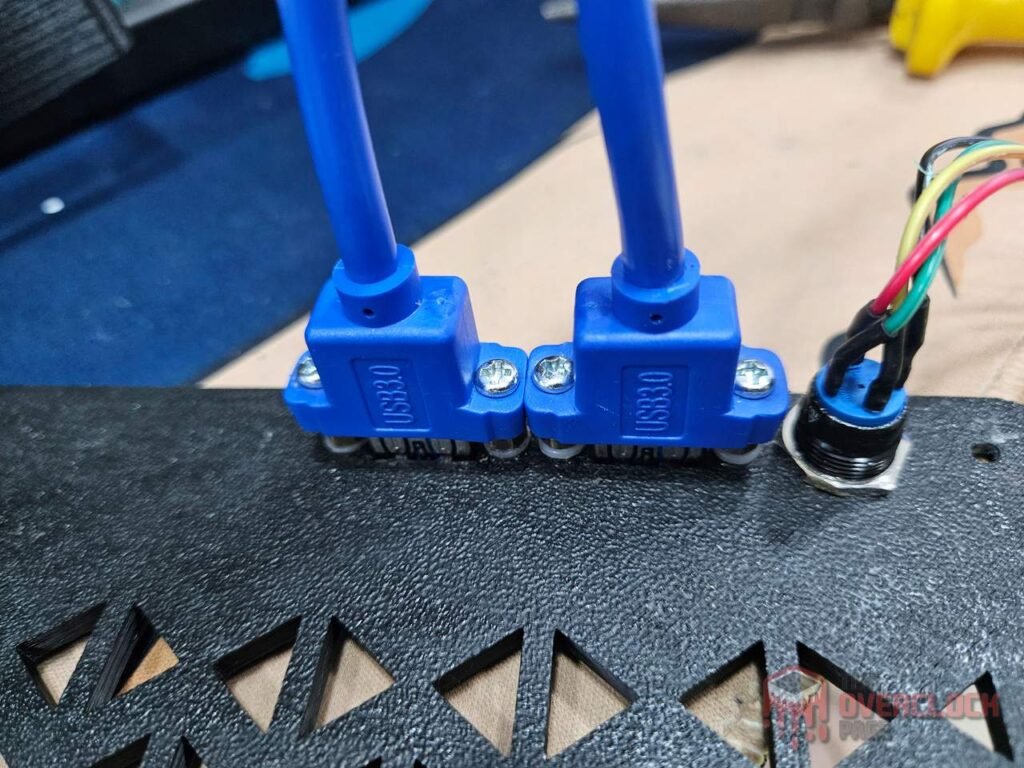

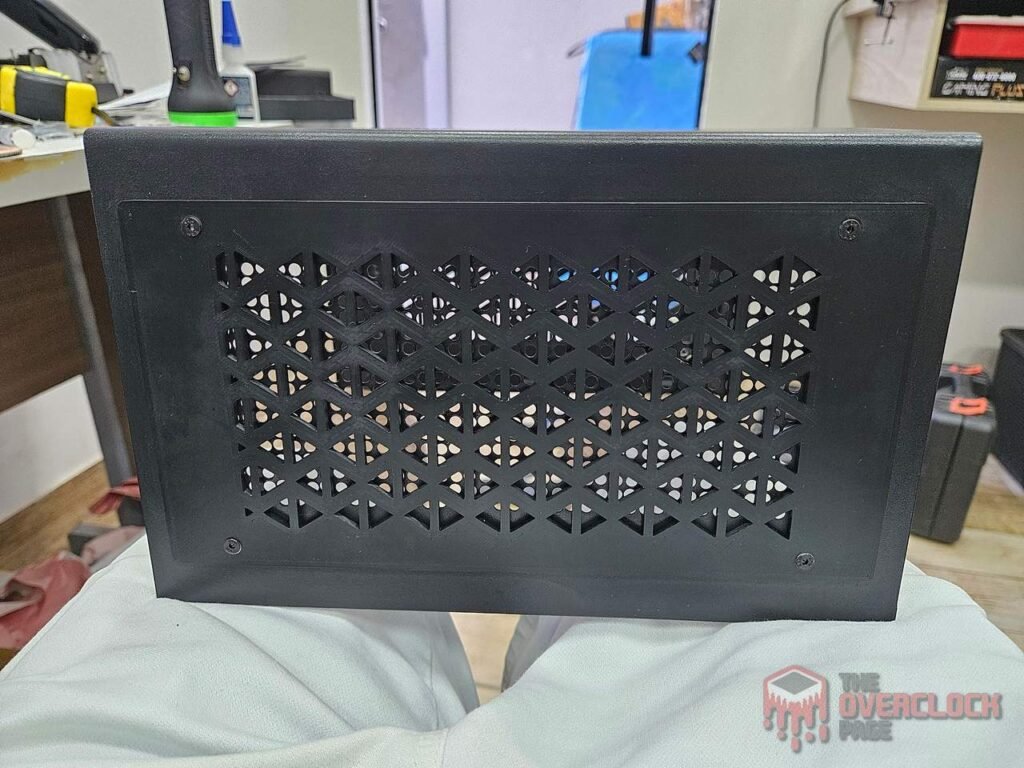

Below are the final versions for the models, which, as I will show later, had a previous version that presented a series of design issues, such as in the positioning and fixation of the USBs, as well as needed cut in the frame, which forced me to do this second version. In the end, it wasnt a bad thing as I also made adjustments to the aesthetics of the piece.

The parts were printed in ABS plastic due to its greater resistance to high temperatures. It’s worth noting that the radiator’s hot air exhaust is done through the front, so it will be exposed to high temperatures for most of the time.

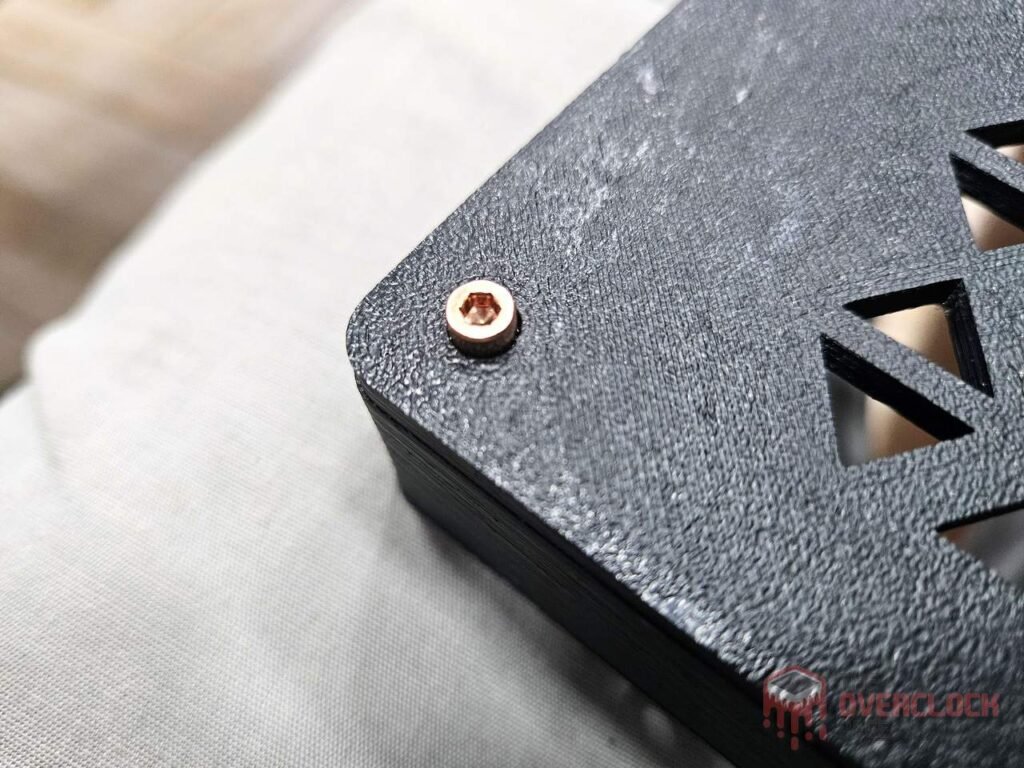

A nice detail are the copper screws on the front, giving a sophisticated touch to the case. 🙂

Now, the final version, with all the flaws corrected in the model, everything fits perfectly now! A bonus for the 2mm copper trim as a finishing touch on the front, which together with the screws, ended up increasing the design’s value by over 1000% for the case! 🙂

And finally, here’s how the case looks with the new front installed.

Adapting Sides to the New Reality?

One of the standout mods in the earlier version of this case were the 120mm fans mounted on the sides. However, over time, they proved to be quite bulky and a hassle to deal with.

With the new front, this extra ended up clashing with the design, so another solution was needed. Ideally, I wanted to keep at least one intake fan inside, which isn’t feasible with 120mm fans but is perfectly possible with a 92mm fan.

That said, to cover the fan holes, I modeled a part following the same front panel design. These pieces were printed in black ABS plastic and screwed onto the sides of the case.

Bonus: Hot Air in Radiator Intake – An Attempt to Solve it…

One of the most noticeable differences between the RX 6700 XT and RX 6800 XT is the size of the PCB. Although the latter fits inside the Sugo case, it creates an issue: The VRM ends up positioned directly in line with the radiator fan, which in this case works better with intake on the inside side, resulting in the air being heated quite a bit and leading to GPU temperatures approaching 78°C after extended gaming sessions.

There are several possible solutions to this problem. One approach could be creating a duct for cold air intake from either the sides or the top, but this would heavily rely on 3D printing and it’s unlikely that the first prototype would be the final version due to limited space inside the case and a high chance of errors.

Another approach is placing some insulating material between the GPU and the radiator to reduce the temperature by isolating the air from the heat source, and it’s exactly this path I ended up taking with a strategically placed neoprene sheet.

As I will show ahead, the results were positive for the GPU but negative for memories and VRM, which recorded a slight temperature increase, albeit remaining within safe levels. For now, this is the solution that stayed, in the near future I might revisit this and make changes. 😉

It is ready!

After all those steps and details, the final result! In the gallery below you can see how the modified Sugo SG13 turned out. Despite personally finding its original design interesting, the new front and sides added a lot to the case’s appearance, giving it a major upgrade overall. 🙂

Now that the case presentation is done, it’s time to showcase the hardware of this PC! 😀

Computer hardware

CPU: AMD Ryzen 9 7900 (Thanks AMD!)

MOBO: GIGABYTE B650I Aorus Ultra

RAM: 2x48GB Kingston Fury Renegade 6400CL32 (Thanks Kingston!)

GPU: Powercolor RX 6800 XT Red Devil

PSU: Thermalright TR-TGFX850

COOLING: Barrow LTPRP-04 + Barrow Dabel-60A 120 + Freezemod GPU Block + EK-Tube ZMT + 2x fans Noctua NF-A12x15-PWM + Noctua NF-A9x14 HS-PWM chromax.black.swap + ID.Cooling NO-8010-PWM

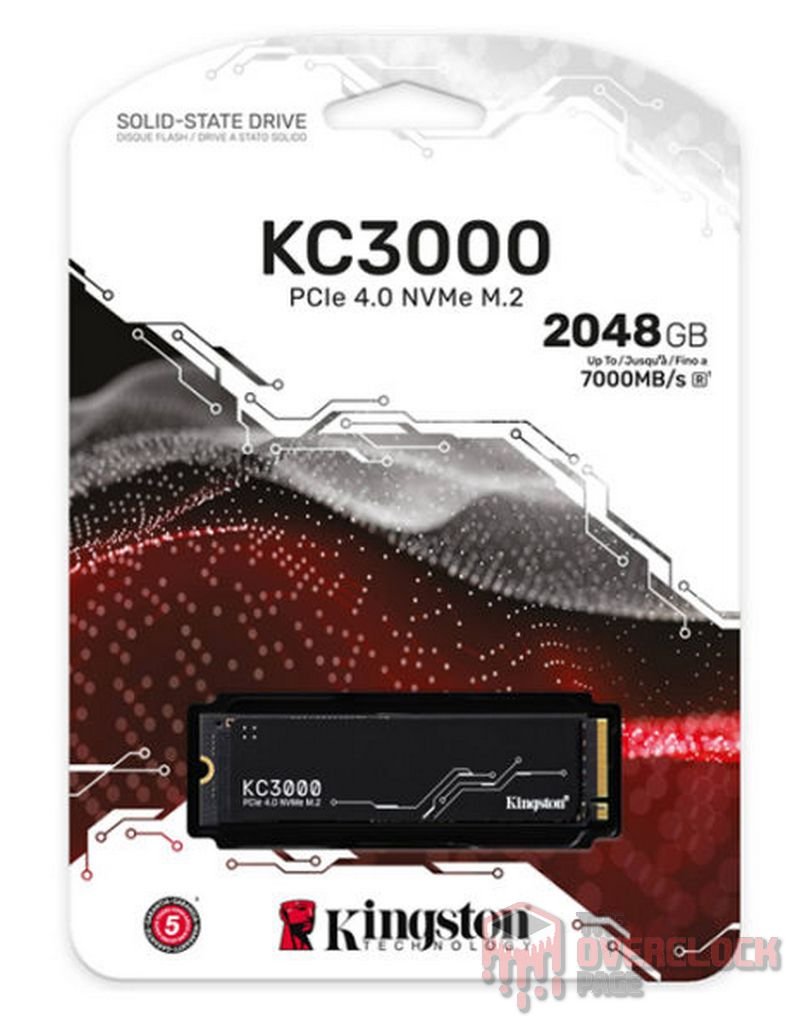

SSD: Kingston KC3000 2 TB (Thanks Kingston!) + Netcore 2 TB (Thanks Netcore!) + Hikvision E3000R 1 TB

Test objectives:

Check if the custom coolers for RX 6800 XT work and evaluate the performance of the custom water cooling loop in the Silverstone Sugo SG13 with the new modifications. More details about the tests are included in the following texts.

Results:

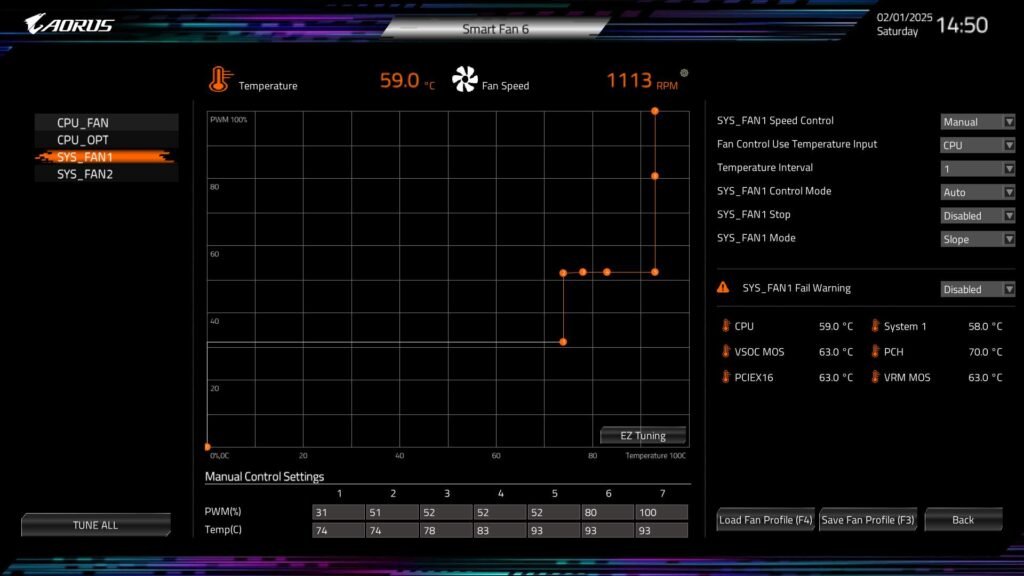

The first thing done after assembling and installing the system was adjusting the fan rotation curve since they were replaced with different Noctua models. An external controller with a water temperature sensor from the loop was used to regulate the two Noctua NF-A12x15-PWM radiator fans, which were set to 30% rotation when water reaches 38°C. The fans start accelerating their rotation from 43°C and reach maximum speed at 57°C.

Below you can see how the adjustment turned out, remembering that this motherboard uses Tctl reading as the basis for curve operation.

Additionally, several optimizations were made with PBO, setting TDP to just 55W, FCLK at 2133 MHz, RAM @ 6000 MT/s CL30 UCLK 1:1, and fine adjustments to some voltages, for example, VDDSOC was stable at only 1.13V even with 96GB of RAM.

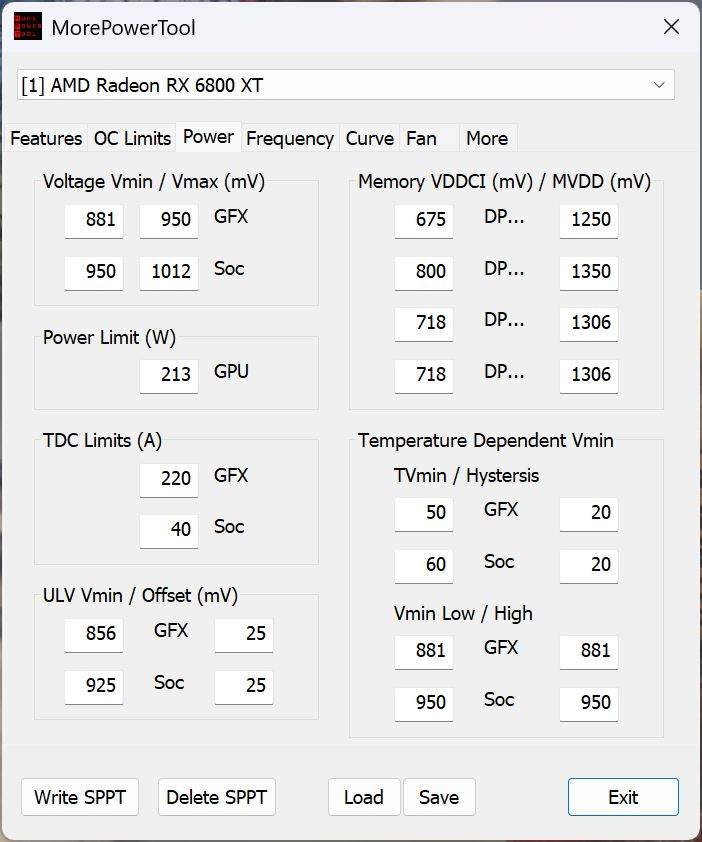

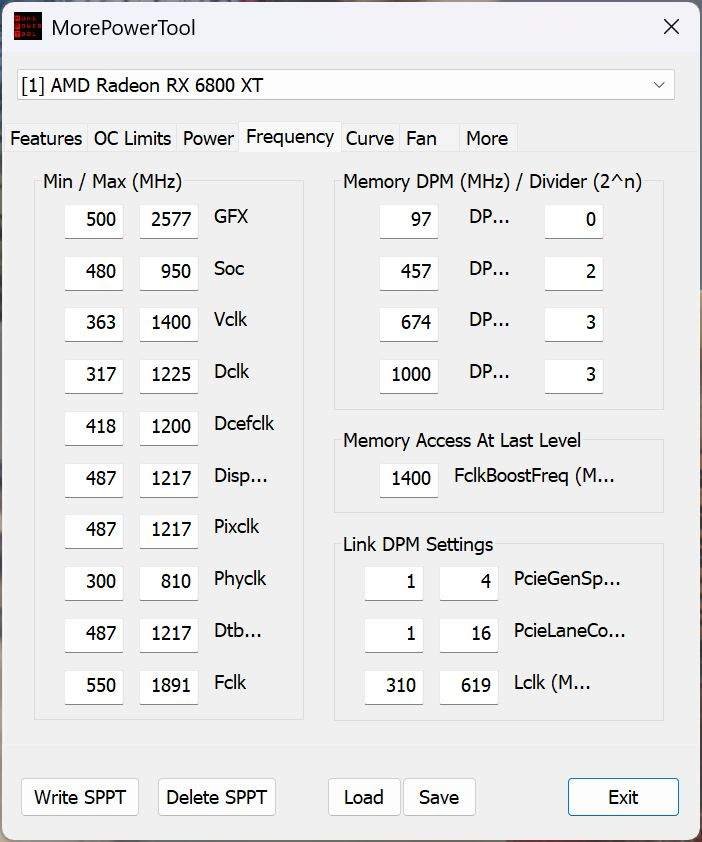

For the RX 6800 XT, undervolting was done using MPT, reducing the GPU’s standard voltage to just 950mV, SOC to 1012mV, and memory to 1306mV. Despite these reductions, it still achieved 2300 MHz in games, with performance virtually identical to the stock card, but consuming less than 200W under load!

Temperatures:

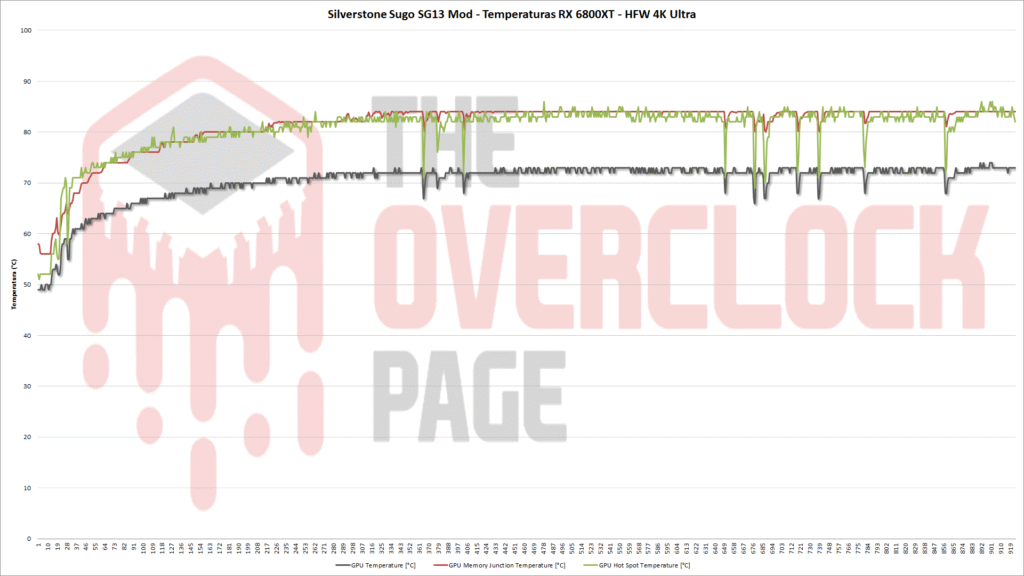

To log the GPU temperature, I opted for a realistic scenario by playing Horizon: Forbidden West for half an hour while monitoring with HWiNFO and using ElmorLabs KTH-USB to record ambient temperature, which was 29.4 ºC.

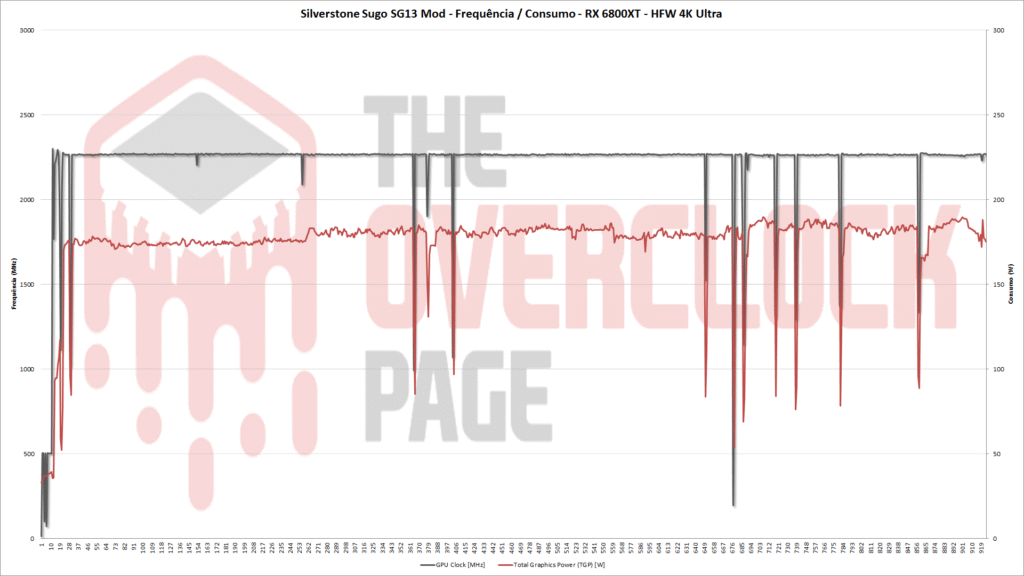

The GPU frequency remained surprisingly stable, fluctuating between 2270 and 2300 MHz, with consumption below 190W, all thanks to the magic of undervolting!

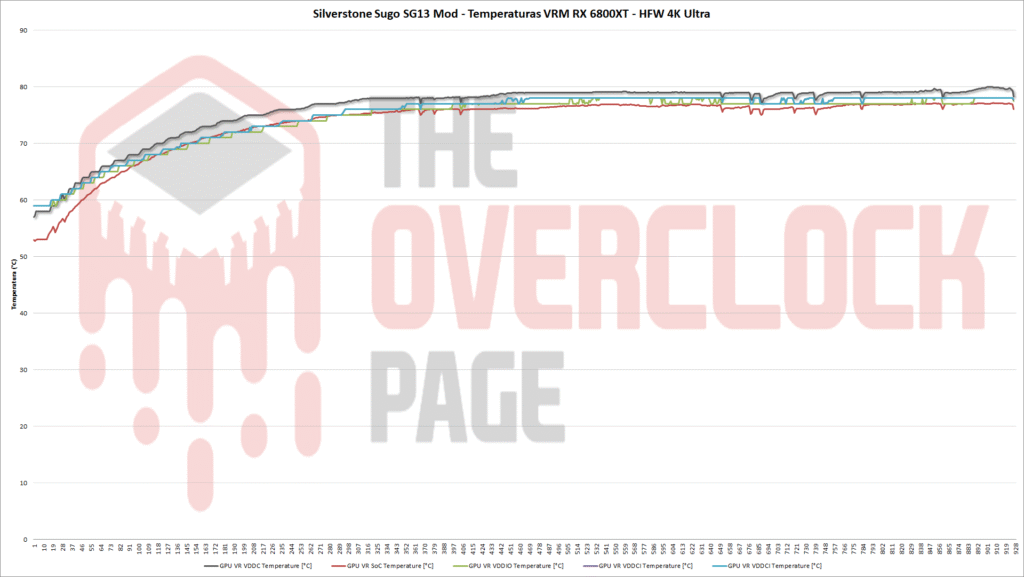

Regarding its temperatures, the GPU peak was 73ºC, VRAM at 83ºC, Hot Spot at 85ºC, while the VRMs were near 78ºC.

While these marks are far from what we’re accustomed to seeing in water-cooled systems, it’s important to note that we’re limited to just a 120mm x 60mm radiator handling a total dissipation of around 260W, all this with only two slim fans adjusted to keep noise levels acceptable. Considering these factors, these temperatures are similar to those observed with this 6800 XT using the original cooler without undervolting and can be considered perfectly safe.

As for the CPU, it had its TDP set to just 55W, which slightly sacrificed multi-thread performance, but ended up giving a margin of up to 15W from the stock settings. It’s worth noting that even in a game like HFW, which isn’t very CPU-intensive, the R9 7900 ends up using the entire PPT standard margin, with negligible performance gains, justifying this TDP concession. With this adjustment, the CPU temperature peaked at 77 ºC during gameplay.

Lastly but not least importantly, the water temperature reached a maximum of 54 ºC, which although slightly elevated, is still below the theoretical limit of 60 ºC. This could potentially degrade certain types of pumps and hoses made from materials that can’t handle higher temperatures, which clearly isn’t the case with the EPDM tubing used here, but could be an issue for the integrated CPU pump DDC.

Conclusion:

Finalizing another chapter in the Sugo SG13 saga, with some effort and optimization, it was possible to install a high-end GPU inside a compact 11.5L case and achieve satisfactory results in terms of noise levels and temperatures, despite being constrained by a relatively small radiator.

Regarding the custom heatsinks for the VRAM and VRM of the graphics card, they performed exceptionally well, handling the task with plenty of margin, as expected given the robust VRM on a board that underwent heavy undervolting. The solution for the VRAM also proved functional, without significantly impacting GPU performance.

From an aesthetic standpoint, the new front panel and sides elevated the visual appeal of the SG13, showcasing just a glimpse of what 3D printing can achieve!

And that’s it for now! The next steps involve installing a more sophisticated fan controller, possibly making additional hardware changes, and exploring further 3D-printed upgrades, which I will detail in a future post. 🙂